Introduction

For a primal linear program defined by

\[\begin{align} &\text{maximize}&\pmb c^\top \pmb x\\\ &s.t. &\pmb A\pmb x\le \pmb b\\\ &&\pmb x\ge\pmb 0 \end{align}\]the dual takes the form

\[\begin{align} &\text{minimize}&\pmb b^\top \pmb y\\\ &s.t. &\pmb A^\top \pmb y\ge \pmb c\\\ &&\pmb y\ge\pmb 0 \end{align}\]This is called the symmetric dual problem. There are two other dual problems listed here. For simplicity, we only discuss the symmetric dual problem.

Connection between the primal and the dual

Well, this is how I build the connection between the primal and the dual as I found the dual extremely unintuitive in the first place.

Write down the Lagrangian of the primal

\[\begin{align} \max_{\pmb x}\min_{\pmb y}\pmb c^\top\pmb x+\pmb y^\top(\pmb b-\pmb A\pmb x)=\max_{\pmb x}\min_{\pmb y}\pmb y^\top\pmb b+(\pmb c^\top-\pmb y^\top \pmb A)\pmb x\le \min_{\pmb y}\max_{\pmb x}\pmb y^\top\pmb b+(\pmb c^\top-\pmb y^\top \pmb A)\pmb x \end{align}\]where we apply the max-min inequality in the last inequality. Leftmost maximin is the Lagrangian of the primal and the rightmost minimax is that of the dual. Note that the above inequality also implies the weak duality defined below by noticing that, at equilibrium \(\pmb y^\top(\pmb b-\pmb A\pmb x)=\pmb 0\) and \(\pmb x^\top(\pmb c-\pmb A\pmb y)=\pmb 0\)

Weak Duality

Theorem 1. For any feasible solution \(\pmb x\) and \(\pmb y\) to primal and dual linear programs, \(\pmb c^\top \pmb x\le \pmb b^\top \pmb y\).

Proof: Multiplying both sides of \(\pmb A\pmb x\le \pmb b\) by \(\pmb y^\top\ge \pmb 0\), we have \(\pmb y^\top \pmb A\pmb x\le \pmb y^\top \pmb b\). Since \(\pmb A^\top \pmb y\ge \pmb c\), we have \(\pmb c^\top \pmb x\le \pmb y^\top \pmb A\pmb x\le \pmb y^\top \pmb b\).

There are two immediate implication of weak duality:

- If both \(\pmb x\) and \(\pmb y\) are feasible solutions to the primal and dual and \(\pmb c^\top \pmb x=\pmb b^\top \pmb y\), then \(\pmb x\) and \(\pmb y\) must be optimal solutions

- If the optimal profit in the primal is \(\infty\), then the dual must be infeasible. If the optimal cost in the dual is \(-\infty\), then the primal must be infeasible

The weak duality always holds regardless whether the primal is concave or not.

Strong Duality

Theorem 2. The duality has an optimal solution if and only if the primal does. If both \(\pmb x^*\) and \(\pmb y^*\) are optimal solutions to the primal and dual, then \(\pmb c^\top \pmb x^*=\pmb b^\top \pmb y^*\).

The strong duality only holds when the primal is concave.

To prove strong duality, we first introduce Farkas’ Lemma and its variant.

Farkas’ Lemma

Lemma 1. Let \(\pmb A\in\mathbb R^{m⨉ n}\) and \(\pmb b\in\mathbb R^m\). Then exactly one of the following two assertions is true:

- There exists an \(\pmb x\in\mathbb R^n\) such that \(\pmb A\pmb x=\pmb b\) and \(\pmb x\ge 0\)

- There exists a \(\pmb y\in\mathbb R^m\) such that \(\pmb A^\top\pmb y\ge \pmb0\) and \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y<0\)

Proof: If both \((1)\) and \((2)\) hold, then \(0>\pmb b^\top \pmb y=\pmb y^\top \pmb A\pmb x\ge 0\), which is a contradiction. Now we prove that if 1 is false then 2 is necessarily true.

Define

\[\begin{align} C(\pmb A)=\{\pmb q\in\mathbb R^m:\exist\pmb x\ge \pmb 0\ \pmb q=\pmb A\pmb x\} \end{align}\]Note that \(C\) is a convex set: for \(\pmb q_1,\pmb q_2\in C\), there exists \(\pmb x_1,\pmb x_2\) such that \(\pmb q_1=\pmb A\pmb x_1\) and \(\pmb q_2=\pmb A\pmb x_2\), and for any \(t\in[0,1]\) we have

\[\begin{align} t\pmb q_1+(1-t)\pmb q_2=t\pmb A\pmb x_1+(1-t)\pmb A\pmb x_2=\pmb A(t\pmb x_1+(1-t)\pmb x_2)\in C \end{align}\]Since 1 is false \(b\notin C\). From the separating hyperplane theorem, we know there exists \(\pmb y\in\mathbb R^m\) such that \(\pmb A^\top\pmb y\ge \pmb0\) and \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y<0\).

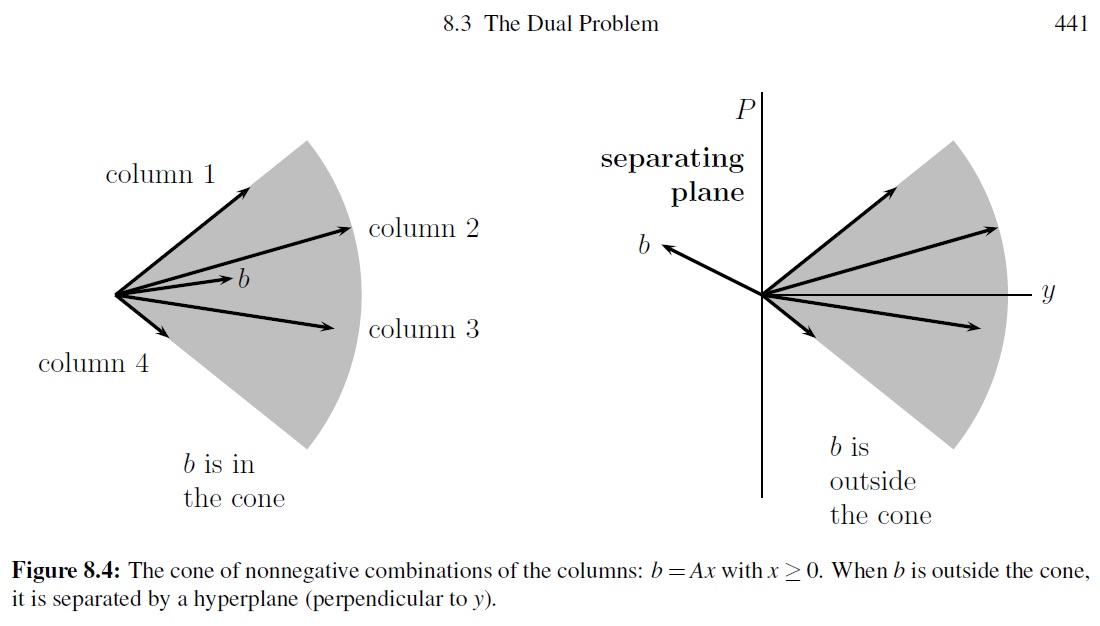

Geometric interpretation. Farkas’ lemma equally says that either \(\pmb b\) in \(C(\pmb A)\) or there exists a hyperplane \(P={\pmb x\vert \pmb y^\top \pmb x=0}\) that separates \(\pmb b\) and \(C(\pmb A)\). If \(\pmb b\) is not in \(C(\pmb A)\), then we can compute \(\pmb y\) as the vector orthogonal to the hyperplane. The following figure visualizes these two cases

A Variant of Farkas’ Lemma

Lemma 2. Let \(\pmb A\in\mathbb R^{m⨉ n}\) and \(\pmb b\in\mathbb R^m\). Then exactly one of the following two assertions is true:

- There exists an \(\pmb x\in\mathbb R^n\) such that \(\pmb A\pmb x\le\pmb b\)

- There exists a \(\pmb y\ge \pmb 0\) such that \(\pmb A^\top\pmb y= \pmb0\) and \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y=-1\)

Proof: By multiplying both sides of \(\pmb A\pmb x\le\pmb b\) by \(\pmb y^\top\), it is easy to see that both cases cannot hold simultaneously.

If case \((1)\) fails to hold, there is no \(\pmb x^+,\pmb x^-\in\mathbb R^n\) and \(\pmb s\in\mathbb R^m\) such that \(\begin{bmatrix}\pmb x^+\\pmb x^-\\pmb s\end{bmatrix}\ge \pmb 0\), and

\[\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix} \pmb A&-\pmb A&\pmb I_m \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}\pmb x^+\\\\pmb x^-\\\\pmb s\end{bmatrix}= \pmb b\\\ \end{align}\]By Farkas’ Lemma, there exists \(\pmb y\in \mathbb R^m\) such that

\[\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix}\pmb A& -\pmb A&\pmb I_m\end{bmatrix}^\top \pmb y \ge\pmb 0,\quad \pmb b^\top\pmb y< 0 \end{align}\]which gives us \(\pmb y\ge \pmb 0\) and \(\pmb A^\top\pmb y\ge \pmb 0,-\pmb A^\top\pmb y\ge \pmb 0\Rightarrow\pmb A^\top\pmb y=\pmb 0\). Because \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y< 0\) and the magnitude of \(\pmb y\) does not affect the results, we can scale \(\pmb y\) such that \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y=-1\).

If case \((2)\) fails to hold, there is no \(\pmb y\in \mathbb R^m\) such that

\[\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix} \pmb A& \pmb I_m \end{bmatrix}^\top \pmb y \ge \pmb 0,\quad \pmb b^\top \pmb y=-1 \end{align}\]By Farkas’ Lemma, there exists \(\pmb x\in \mathbb R^n, \pmb z\in\mathbb R^m\) such that \(\begin{bmatrix}\pmb x\\pmb z\end{bmatrix}\ge \pmb 0\)

\[\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix} \pmb A& \pmb I_m \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \pmb x\\\\pmb z \end{bmatrix}=\pmb b \end{align}\]Therefore, \(\pmb A\pmb x+\pmb z=\pmb b\) and case \((1)\) holds.

Proof of Strong Duality

Let

\[\begin{align} \pmb{\hat A}=\begin{bmatrix}\pmb A\\\-\pmb c^\top\end{bmatrix},\pmb{\hat b}=\begin{bmatrix}\pmb b\\\-(\tau+\epsilon)\end{bmatrix} \end{align}\]where \(\tau=\pmb c^\top\pmb x^*\) is the optimal value of the primal, \(\epsilon\ge 0\) is an arbitrary small value. Because \(\tau\) is the optimal value, there is no feasible \(\pmb x\) such that \(\pmb c^\top\pmb x=\tau+\epsilon\). Therefore, there is no \(\pmb x\in\mathbb R^n\) such that

\[\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix}\pmb A\\\-\pmb c^\top\end{bmatrix}\pmb x\le \begin{bmatrix}\pmb b\\\-(\tau+\epsilon)\end{bmatrix} \end{align}\]By Lemma 2, there exists \(\pmb{\hat y}=\begin{bmatrix}\pmb y\\ \alpha\end{bmatrix}\ge\pmb 0\), such that

\[\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix}\pmb A^\top&-\pmb c\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\pmb y\\\\alpha\end{bmatrix}=\pmb 0, \quad \begin{bmatrix}\pmb b^\top&-(\tau+\epsilon)\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\pmb y\\\\alpha\end{bmatrix}<0\\\ \end{align}\]Thus, we have

\[\begin{align} \pmb A^\top\pmb y=\alpha\pmb c,\quad \pmb b^\top\pmb y<\alpha(\tau+\epsilon) \end{align}\]If \(\alpha=0\), then the dual is either infeasible or unbounded—for any feasible solution to the dual \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y_*\), we can always find a smaller feasible solution \(\pmb b^\top(\pmb y_*+\pmb y)\) because \(\pmb A^\top\pmb y= \pmb 0\) and \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y<0\). Therefore, \(\alpha>0\) and by scaling \(\pmb {\hat y}\), we may assume that \(\alpha=1\). So \(\pmb A^\top \pmb y\ge \pmb c\) and \(\pmb b^\top\pmb y\le \tau+\epsilon\). By the weak dual theorem, we have \(\tau= \pmb c^\top \pmb x\le\pmb b^\top\pmb y\le\tau+\epsilon\). Since \(\epsilon\) can be arbitrarily small, we have \(\pmb c^\top \pmb x=\pmb b^\top\pmb y\).

Miscellanea

Here, we prove KKT conditions using Farkas’ Lemma

KKT conditions

KKT conditions: Suppose that \(f,g^1,g^2,g^M\) are differentiable functions from \(\mathbb R^N\) to \(\mathbb R\). Let \(\pmb x^*\) be the point that maximizes \(f\) subject to \(g^i(\pmb x)\le 0\) for each \(i\), and assume the first \(k\) constraints are active and \(\pmb x^*\) is regular. Then there exists \(\pmb y\in\mathbb R^k\) such that \(\pmb y\ge \pmb 0\) and \(\nabla f(\pmb x^*)=y_1\nabla g^1(\pmb x^*)+…+y_k\nabla g^k(\pmb x^*)\)

Proof: Let \(\pmb c=\nabla f(\pmb x^*)\). The directional derivative of \(f\) in the direction of vector \(\pmb z\) is \(\pmb z^\top\pmb c\). Because \(\pmb x^*\) is the maximum point, every feasible direction \(\pmb z\) must have \(\pmb z^\top\pmb c < 0\). Let \(\pmb A\in\mathbb R^{k\times N}\) be the matrix whose \(i\)th row is \((\nabla g^i(\pmb x))^\top\). Then a direction \(\pmb z\) is feasible if \(\pmb A\pmb z\le 0\). As \(\pmb z^\top\pmb c<0\) and \(\pmb A\pmb z\le 0\) violate Farkas’ case \((2)\) , there is a \(\pmb y\ge \pmb 0\) such that \(\pmb A^\top\pmb y=\pmb c\).

Thoughts

In the above proofs, we saw several tricks used in linear programming.

- We can convert an inequality to equality with recourse to a slack variable. For example, \(\pmb A\pmb x\le\pmb b\) is equivalent to \(\begin{bmatrix}\pmb A&\pmb I\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\pmb x\\pmb s\end{bmatrix}=\pmb b\) for \(\pmb s\ge \pmb0\).

- To get \(\pmb y^\top\pmb A=\pmb0\), we construct and prove \(\begin{bmatrix}\pmb A& -\pmb A\end{bmatrix}^\top\pmb y\ge 0\).

- When we have \(\pmb y\ge \pmb 0\) and \(\pmb A^\top \pmb y\ge \pmb 0\), we can combine them in a single inequality \(\begin{bmatrix}\pmb A^\top\\pmb I\end{bmatrix}\pmb y\ge 0\).

- To prove \(\pmb c^\top\pmb x=\pmb y^\top\pmb b\) with known \(\pmb c^\top\pmb x\le\pmb y^\top\pmb b\), we show \(\pmb y^\top\pmb b\le \pmb c^\top\pmb x+\epsilon\) for arbitrary \(\epsilon\).

References

https://web.stanford.edu/~ashishg/msande111/notes/chapter4.pdf

http://www.ma.rhul.ac.uk/~uvah099/Maths/Farkas.pdf

https://people.seas.harvard.edu/~yaron/AM221-S16/lecture_notes/AM221_lecture4.pdf