Introduction

Classic deep reinforcement learning agents maximize cumulative rewards using transitions collected along the way. However, environments in general contain a much wider variety of possible training signals. In this post, we discuss a novel algorithm, named UNsupervised REinforcement and Auxiliary Learning (UNREAL), which utilizes these auxiliary training signals to speed up the learning process and potentially gain better performance.

Unsupervised Reinforcement and Auxiliary Learning

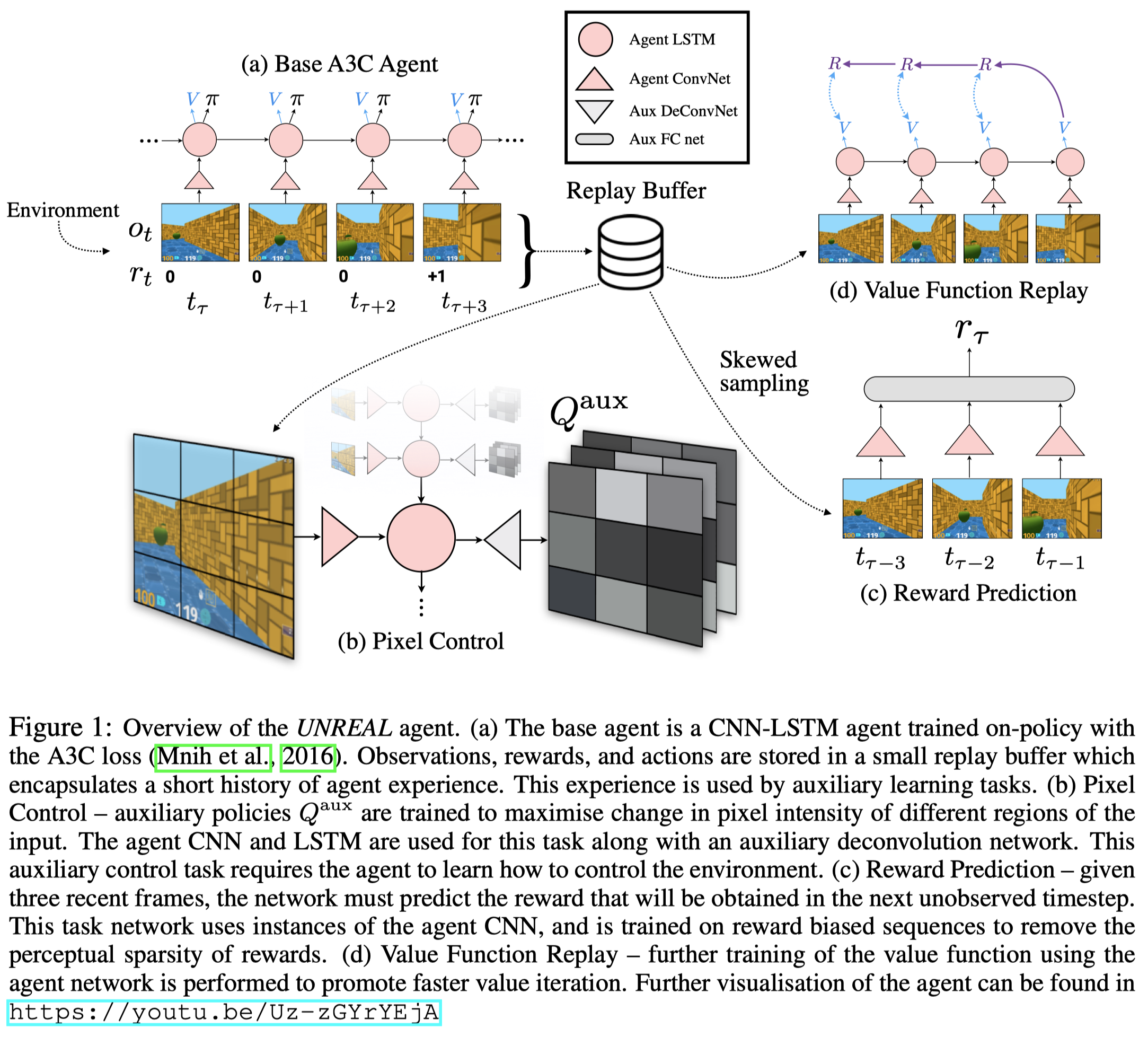

Put aside the auxiliary tasks, UNREAL uses the same architecture as A3C(Figure 1.a) consisting of a convolutional network, a LSTM, and two fully connected layers. The convolutional network encodes the image, extracting a low-dimensional feature vector, on which the LSTM further summarizes the contextual information. The last two fully connected layers are for policy \(\pi\) and value function \(V\), respectively. The loss function could be either the REINFORCE loss or the PPO loss.

In the rest of this post, we will see what auxiliary tasks it adopts and how they improve the performance.

Auxiliary Pixel Control Tasks

In addition to the original control task that maximizes the cumulative extrinsic rewards, an auxiliary control task is formulated to boost the learning process. The auxiliary control tasks, based on the observation that big changes in the perceptual stream often correspond to important events in an environment, defines a pseudo-reward function as pixel changes in each cell. That is, average absolute pixel changes in each cell of an \(N\times N\) non-overlapping grid placed over the input image(Figure 1.b), where the average is taken over both pixels and channels in the cell. The auxiliary network head(a deconvolutional network) outputs an \(N\times N\times \vert \mathcal A\vert \) tensor \(Q^{\mathrm{aux}}\), where \(N\) is the number of grids in a row/column and \(Q^{\mathrm{aux}}(s.a,i,j)\) represents the network’s current estimate of the discounted expected change in cell \((i,j)\) of the input after taking action \(a\). This network is trained by an \(n\)-step \(Q\)-learning parameterized as the dueling DQN.

Auxiliary Reward Prediction Tasks

In order to remove the perceptual sparsity of rewards, an auxiliary task of reward prediction is proposed, which predicts the onset of immediate reward given some historical context. The task is trained on sequences \(S_\tau=(s_{\tau-k},\dots, s_{\tau-1})\) to predict the reward \(r_\tau\). \(S_\tau\) is sampled from the experience in a skewed manner so as to overrepresent rewarding events. Specifically, we sample such that zero rewards and non-zero rewards are equally represented. In their experiments, the reward prediction is trained to minimize a classification loss across three classes (zero, positive, or negative reward).

Note that the LSTM layer is not trained in this task. Instead, the authors use a simpler feedfoward network that concatenates a stack of state \(S_\tau\) after being encoded by the agent’s ConvNet (Figure 1.c). The idea is to simplify the temporal aspects of the prediction task in both the future direction (focusing only on immediate reward prediction rather than long-term returns) and past direction (focusing only on immediate predecessor states rather than the complete history).

Value Function Replay

An experience replay is used to increase the efficiency and stability of the above auxiliary control tasks. It also provides a natural mechanism for skewing the distribution of reward prediction samples towards rewarding events: we simply split the replay buffer into rewarding and non-rewarding subsets, and replay equally from both subsets.

Furthermore, the replay buffer is also used to perform value function replay in the same way as \(Q\)-learning updates. That is, use the data from the replay buffer to perform additional training on the value function in A3C. Such extra critic updates have been shown to speed up the algorithm convergence.

Summary

Now we write down all losses used in UNREAL.

\[\begin{align} \mathcal L_{UNREAL}(\theta)&=\mathbb E[\mathcal L_{\pi}+\lambda_{V}\mathcal L_{V}+\lambda_{PC}\sum_c\mathcal L_{PC}+\lambda_{RP}\mathcal L_{RP}]\\\ where\quad \mathcal L_\pi&=-A(s_t,a_t)\log\pi(a_t|s_t;\theta)-\alpha\mathcal H(\pi(a_t|s_t;\theta))\\\ \mathcal L_{V}&=\big(R_{t:t+n}+\gamma^{n-1}V(s_{t+n};\theta^-)-V(s_t;\theta)\big)^2\\\ \mathcal L_{PC}&=\big(R_{t:t+n}+\gamma^{n-1}\max_{a'} Q(s_{t+n},a';\phi^-)-Q(s_t,a_t;\phi)\big)^2\\\ \mathcal L_{RP}&=y_\tau\log f_r(S_{\tau};\psi) \end{align}\]where only the A3C loss is optimized with data collected by the online policy, all others are optimized with data sampled from the replay buffer. Once again, the reward prediction is optimized with rebalanced replay data, while value function replay and auxiliary control learning are optimized with data uniformly sampled. Both \(\lambda_{V}\) and \(\lambda_{RP}\) are set to \(1\) in their experiments, while \(\lambda_{PC}\) is sampled from log-uniform distribution between \(0.01\) and \(0.1\) for Labyrinth and \(0.0001\) and \(0.01\) for Atari (since Atari games are not homogeneous in terms of pixel intensities changes, thus we need to fit this normalization factor)

Experimental Results

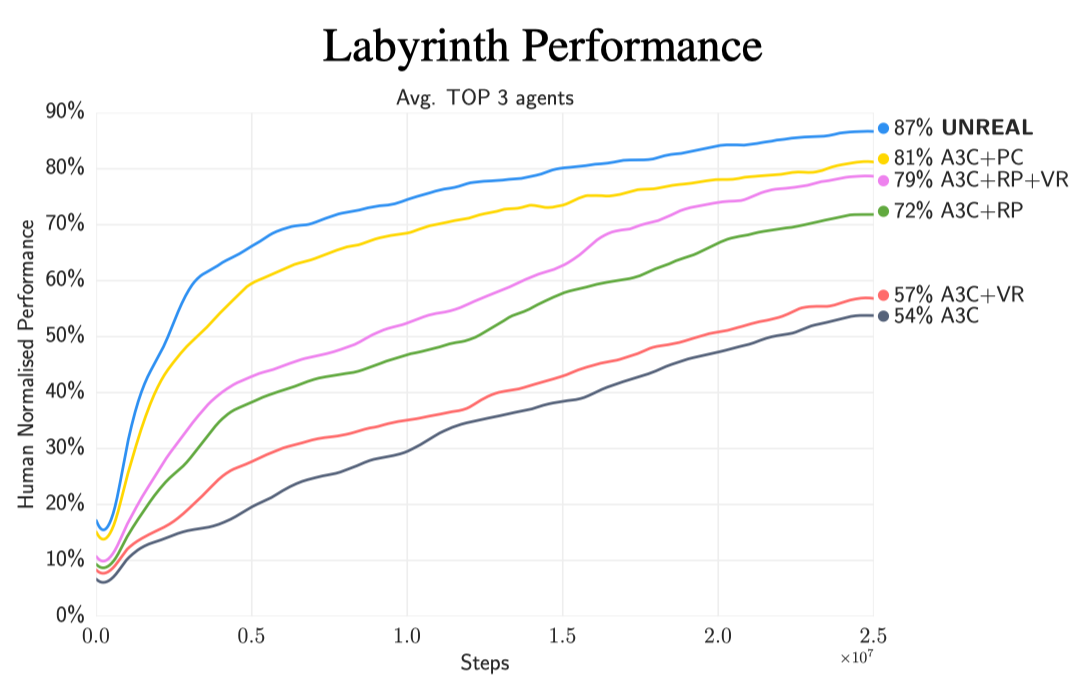

The following figure shows the contribution of each component in Labyrinth. Note that its the average of the top 3 agents.

We can see that most performance gain comes from the pixel control, and then the reward prediction.

Other kinds of auxiliary task

In the above video, Abbeel compares the pixel control with feature control, input change prediction and etc, finding that pixel control, at least in their experiments, outperforms all of them. An intuition of why the pixel control performs better than the input change prediction is that the input change prediction tries to predict how the world works, while the pixel control predicts how the agent affects the world. The latter’s what really matters for learning to achieve the task we care about.

References

Max Jaderberg et al. Reinforcement Learning with Unsupervised Auxiliary Tasks