What’s This Post about?

After reading this post, you might get a sense of

- What the parameters in SVMs mean, and how to tune them when using off-the-shelf SVM packages.

- How SVMs work in perfectly linearly separable case and linearly separable case with error

- How SVMs deal with non-linearly separable case using kernel, why kernels can help SVMs separate non-linearly separable data

- Why small \( \gamma \) leads to high variance and low bias in the Gaussian kernel and in the polynomial kernel

- When to choose the Gaussian kernel, and when the polynomial kernel

- How to use SVMs to solve multiclass problem

- How to solve an optimization problem with constraints using the method of Lagrange Multipliers

Introduction

An SVM tries to construct a hyperplane or set of hyperplanes, which can be used for classification or regression. It distinguishes a good hyperplane from a bad one by something called margin. In another word, the objective of an SVM is to find a hyperplane or set of hyperplanes which maximize the margin.

Parameters

I place the parameters in the first place because there’re lots of off-the-shelf SVM packages online, one can simply treat SVMs as a black box and apply them with the help of these parameter explanations.

Regularization Parameter \( C \)

Regularization parameter \( C \) scales the penalty for the error: the larger \( C \) is, the less the SVM tolerates training error, which results in high variance and low bias.

Kernel Coefficient \( \gamma \)

The kernel coefficient,,, well, it’s self-explained. Although the kernel could be different, they all follow the same trend: the smaller \( \gamma \) is, the farther the relative (which is something I make up, I’ll explain why I say it’s relative later) influence of a training point reaches. And for a point, the more training points it is influenced by, the less sensitive it is to a noise. Therefore, a small \( \gamma \) leads to high variance and low bias, which has the opposite effect of the regularization parameter \( C \).

Now go grab a coffee, Let’s dive into the detail :-)

Perfectly Linearly Separable Case

If the training data is linearly separable, then we could mathematically describe a binary classification probelm as below

\[\begin{align} \max_{w, b}&M \\\ s.t.\quad{y_i(w \cdot x_i + b)\over\lVert w\rVert} &\ge M, \forall i \end{align}\]where \( (w \cdot x_i + b) / \lVert w\rVert \) is the distance from \( x_i \) to the hyperplane defined by \( w \) and \( b \). \( y_i \) is the label of the training point \( i \), which is either \( 1 \) or \( -1 \), here used to adjust the sign of the vector distance. As we mentioned in the introduction, SVM tries to maximizes the margin \(M\).

Notice that the value of the left side of the constraints is actually independent of the magnitude of \( w \) — \( w \) simply serves as a direction which indicates where the projection of \( x_i \) is. That means we can arbitrarily assign values to \( \lVert w\rVert \), and the result remains the same. By letting \( \lVert w\rVert=1/M \), the above optimization problem now becomes

\[\begin{align} \min_{w, b}&\lVert w\rVert \\\ s.t.\quad y_i(w\cdot x_i + b)&\ge 1, \forall i \end{align}\]Furthermore, it can be rewritten as

\[\begin{align} \min_{w, b}{1\over2}&\lVert w\rVert^2 \\\ s.t.\quad y_i(w\cdot x_i + b)&\ge 1, \forall i \end{align}\]which is a convex optimization problem (quadratic criterion with linear inequality constraints) and can be solved by the Lagrangian. Since perfect linearly separable case is a subset of linearly separable case with error, here I put off the detailed discussion to the next section.

Linearly Separable Case with Error

If the training data is not linearly separable, but could be approximately separated by a hyperplane, we introduce a slack term, \( \zeta_i \), to express the tolerable error. Now the optimization problem becomes:

\[\begin{align} \max_{w, b}&M \\\ s.t.\ &\begin{cases}{y_i(w \cdot x_i + b)\over\lVert w\rVert} \ge M(1-\zeta_i), \forall i\\\ \zeta_i\ge 0, \forall i\\\ \sum\zeta_i \le constant\end{cases} \end{align}\]Here we also bound the total proportion amount of error, \( \sum\zeta_i \). The same discussion in the previous section works here as well, therefore we rephrase the problem as

\[\begin{align} \min_{w, b}&{1\over2}\lVert w\rVert^2 \\\ s.t.\quad&\begin{cases}{y_i(w\cdot x_i + b) \ge 1-\zeta_i, \forall i} \\\ \zeta_i \ge 0, \forall i \\\ \sum\zeta_i \le constant\end{cases} \end{align}\]Since it is reasonable to minimize the error term \( \sum\zeta_i\) as well, we could further reexpress the problem in the equivalent form

\[\begin{align} \min_{w, b}&{1\over2}\lVert w\rVert^2 +C\sum\zeta_i\\\ s.t.\quad&\begin{cases}{y_i(w\cdot x_i + b) \ge 1-\zeta_i, \forall i}\\\ \zeta_i\ge 0, \forall i \end{cases} \tag {1} \end{align}\]where \( C \) is a hyperparameter, which controls the tradeoff between the data loss(\(\sum\zeta_i\)) and the regularization loss(\(\Vert w\Vert^2\)).

The Lagrange function is

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{L}={1\over2}\lVert w\rVert^2+C\sum\zeta_i + \sum \alpha_i[(1-\zeta_i)-y_i(w\cdot x_i + b)]-\sum \mu_i\zeta_i \tag {2} \end{align}\]where \( \alpha_i, \mu_i, \zeta_i\ge 0\ \forall i \). By setting to zero the partial derivative w.r.t parameters \( w \), \( b \), \( \zeta_i \), we get

\[\begin{align} w&=\sum \alpha_iy_ix_i \tag {3}\\\ 0&=\sum \alpha_iy_i \tag {4}\\\ C&=\alpha_i+\mu_i, \forall_i \tag {5} \end{align}\]Plugging them back into the Lagrange function, we have

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{L}=\sum\alpha_i-{1\over2}\sum_i\sum_j\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i\cdot x_j \tag {6} \end{align}\]which gives a lower bound on the objective function,

\[\begin{align} \min_{w, b}{1\over\lVert w\rVert^2} +C\sum\zeta_i \end{align}\]To maximize \( \mathcal{L} \), we set the constraint terms in \( (2) \) to zero(since both are non-positive when the constraints in \((1)\) satisfy) and have

\[\begin{align} \alpha_i[(1-\zeta_i)-y_i(w\cdot x_i + b)]&=0, \forall i \tag {7}\\\ \mu_i\zeta_i&=0, \forall i \tag {8} \end{align}\]Together, \( (3)-(8) \) uniquely characterize the solution to the Lagrange function.

Additional Notes

-

Based on \( (5) \) and \( (8) \), we have \( 0<\alpha_i <C \) for those points on the edge of the margin, where \( \zeta_i=0 \), and \( \alpha_i = C \) for those on the wrong side of the margin, where \( \zeta_i>0 \). Furthermore, \((3)\) and \((7)\) suggest that the parameters \(w\) and \(b\) are uniquely characterized by points with \(\alpha_i\) is nonzero. Therefore, we usually refer to those points as the support vectors as they exclusively describes the model.

-

From \( (7) \) we can see that any of these support points on the edge of the margin \( (\alpha_i>0, \zeta_i=0) \) can be used to solve for \( b \), and we typically use an average of all the solutions for numerical stability.

-

\( (6) \) indicates that the Lagrange function only depends on \( x_i \cdot x_j \), the dot product of support vectors. Moreover, plugging \( (3) \) into the decision rule \( w\cdot x +b \), from which we predict the class of a new point \( x \), we get

again, this is dependent on \( x_i\cdot x \), the dot product of a support vector and the new point. This observation allows SVMs to employ the kernel trick.

Out of topic: Just as a remainder, some literature replaces \(\zeta\) in the objective function with its constraints and thereby rephrases \( (1) \) as a loss function

\[\begin{align} \mathcal L={1\over 2} \lVert w\rVert^2 + C\sum_i \max(0, 1-y_i(w\cdot x_i+b)) \end{align}\]In this way, we can do gradient descent on the weights and bias as we do with neural networks.

Non-linearly Separable Case

It is usual that the data cannot be simply linearly separated. To cope with such situations, SVMs employ something called the kernel trick to transform data into another space (usually higher dimensional space). Thanks to the observation from the note 3: the Lagrange function and the decision rule only depend on the dot product of points. That suggests we don’t really need to calculate the transformation \( \Phi(x_i) \), all we need to do is to calculate the kernel \( K(x_i, x_j)=\Phi(x_i)\cdot \Phi(x_j) \)

Kernel

There are many kernels, here I only address the two most popular kernels and explain some details about them

Gaussian Kernel, aka., Radial Basis Function Kernel

The Gaussian kernel is represented as follows

\[\begin{align} K(x_i, x_j)=\exp(-\gamma\lVert x_i-x_j\rVert^2) \end{align}\]where the kernel coefficient \( \gamma={1\over2\sigma^2} \). With this definition, It is pretty clear that small \( \gamma \) results in high variance, since it’s the reciprocal of variance. Next, I’ll provide some intuition about why the Gaussian kernel works. As for those who want to know why \( \Phi(x_i)\cdot\Phi(x_j) \) could be mathematically addressed by the Gaussian kernel, please refer to this.

For convinence, I rewrite the gaussian function in the general form

\[\begin{align} F(x)=a\exp\left(-{(x-b)^2\over2\sigma^2}\right) \end{align}\]This function has a very nice property that \( F(x) \) gets large when \( x \) gets close to \( b \). Applying this property to the Gaussian kernel, we learn that \( K(x_i, x_j) \) gets large when \( x_i, x_j \) get close to each other. This suggests that the closer \( x_j\) is to \( x_i\), the more \( x_j \) resembles \( x_i\), i.e., the more likely \( x_j\) tends to have the same label as \( x_i \).

Tips: it’s recommended by Professor Andrew Ng to normalize the input data before using the Gaussian kernel.

Polynomial Kernel

The polynomial kernel is addressed as below

\[\begin{align} K(x_i, x_j)=(\gamma x_i\cdot x_j + c)^d \end{align}\]where \( \gamma \) is the kernel coefficient, \( c \) is a constant trading off the influence of higher-order versus lower-order terms in the polynomial, usually set to \( 1 \).

Out of Topic: here’s a question, which confused me for a while when I wrote this post: it is said that the smaller \( \gamma \) is, the farther the relative influence of a training point reaches. Here, however, large \( \gamma \) results in high \( K \) value, and which in turn suggests great influence. Shouldn’t this suggest high variance? Take your time, see if it traps you too.

The key point is to realize that the influence should be relative, not absolute. For example, assuming \( x\cdot x_i=1, x\cdot x_j=2, \gamma=1, c=1, d=2 \), we have

\[\begin{align} K(x, x_i)=(1+1)^2=4\\\K(x, x_j)=(2+1)^2=9 \end{align}\]Now increasing \( \gamma=2 \), we have

\[\begin{align} K(x, x_i)=(2+1)^2=9\\\K(x, x_j)=(4+1)^2=25 \end{align}\]Although \( K(x, x_i) \) increases from \( 4 \) to \( 9 \), the ratio of \( K(x, x_i) \) to \( K(x, x_j) \) actually decrease from \( 0.44 \) to \( 0.36 \). That means \( x \) bears less similarity to \( x_i \) than before and hence the relative influence of \( x_i \) is actually diminished as \( \gamma \) increase.

Gaussian Kernel vs. Polynomial Kernel

The Gaussian kernel is more popular in SVM, while the polynomial kernel is more popular in natural language processing (NLP). The most common \( d \) is \( 2 \), since larger \( d \) tend to overfit on NLP problems.

Also notice, the polynomial kernel may suffer from numeric instablility: when \( x_i\cdot x_j + c<1 \), \( K \) tends to zero with increasing \( d \), whereas \( x_i\cdot x_j + c>1 \), \( K \) tends to infinity.

Multiclass Case

One way SVMs solve a multiclass problem is to train \( n \) SVMs, each distinguishes one class from the rest. At the prediction stage, we pass the features to all SVMs, the one that yields the highest value assigns the class.

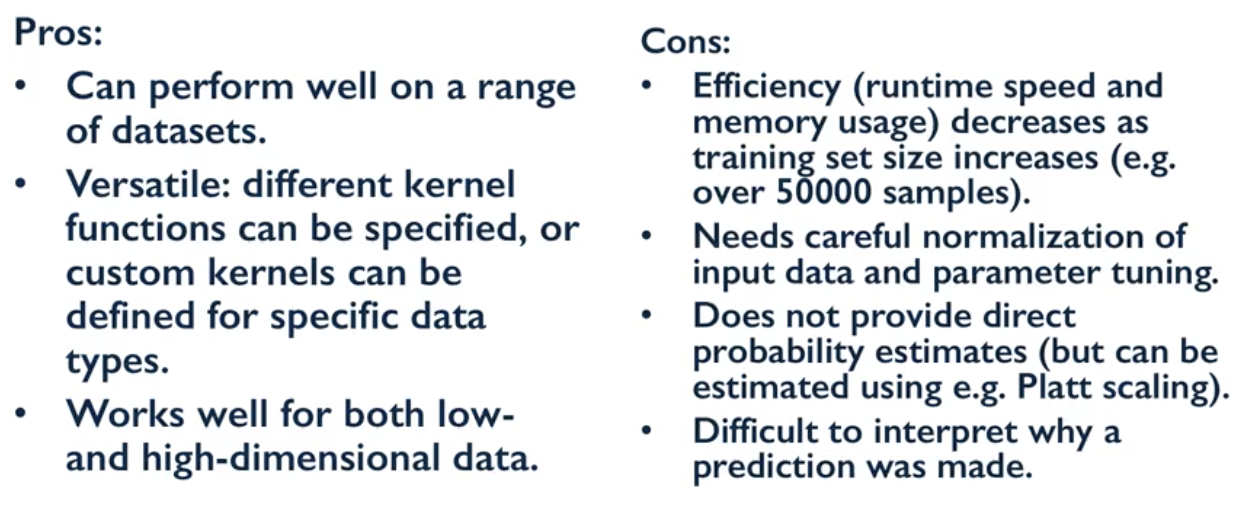

SVM vs Neural Network

The general guideline recommended by Professor Andrew Ng are as below — \( n \) is the number of features and \( m \) is the size of training data

- If \( n \) is large, use neural networks, or SVMs without a kernel. This is because the cost of evaluating kernel methods is linear in the number of training examples

- If \( n \) is small (less than 1,000) and \( m \) is intermediate (around 10,000), go with SVMs with the Gaussian kernel

- If both \( n \) and \( m \) are small, add more features and then use a neural network, or SVM without a kernel

One advantage of SVMs is that it’s a convex optimization problem, which means it doesn’t suffer local minima

Duality

Optimization Problem

The primal optimization problems ask to minimize or maximize a function given some constraints. Mathematically, it’s represented as

\[\begin{align} \max\quad &f(x_1, ..., x_n) & \tag{11} \\\ s.t.\quad &g_i(x_1, ..., x_n)\le 0, &i=1, ..., k\\\ &h_i(x_1, ..., x_n)= 0, &i=1, ..., l\\\ \end{align}\]Solution

Consider the simplest case, where there is only one constraint \(g\): an observation is that when the objective function \( f \) is at a (local) maximum, the contour line for \( f\) will be tangent to the contour for \( g\)—i.e. the gradient of \( f \) is multiple of that of \( g \) at a maximum(see this for an illustrative example). Generalizing this observation to multiple constraints \( g_i \)s and \( h_i\)s, we have the gradient of \( f \) is a linear combination of all the constraints’ gradients, i.e.,

\[\begin{align} \nabla f(x_1, ..., x_n) = \pm\left(\sum_{i=1}^k\alpha_i\nabla g_i(x_1, ..., x_n) + \sum_{i=1}^l\beta_i\nabla h_i(x_1, ..., x_n)\right) \tag{12} \end{align}\]As a result, we define the Lagrangian as

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{L}(x_1, ..., x_n, \alpha_1, ..., \alpha_k,\beta_1,\dots,\beta_l)=\begin{cases} f(x_1, ..., x_n) - \sum_{i=1}^k\alpha_ig_i(x_1, ..., x_n) - \sum_{i=1}^l\beta_ih_i(x_i, ..., x_n)& \color{red}{\text{when } f\text{ is maximized}}\\\ f(x_1, ..., x_n) + \sum_{i=1}^k\alpha_ig_i(x_1, ..., x_n) + \sum_{i=1}^l\beta_ih_i(x_i, ..., x_n)& \color{red}{\text{when } f\text{ is minimized}} \end{cases} \end{align}\]where \( \alpha_i \)s and \( \beta_i \)s are called the dual variables or Lagrange multipliers, and \(\alpha_i\ge0\). The sign of the constraints are chosen so that the Lagrangian is an upper bound when \(f\) is maximized, and a lower bound when \(f\) is minimized–note that all \(g_i\)s are negative. \( (12) \) can be rewritten as

\[\begin{align} \nabla \mathcal{L}(x_1, ..., \alpha_1, ..., \beta_1, ...)=\mathbf0 \end{align}\]expanding \( \nabla \mathcal{L} \), we have

\[\begin{align} \begin{cases}{\partial \mathcal{L}\over \partial x_1}=0\\\ ...\\\ {\partial \mathcal{L}\over\partial \alpha_1}=0\\\ ...\\\ {\partial \mathcal{L}\over\partial \beta_1}=0 \\\ ...\end{cases}\tag{13} \end{align}\]By solving \( (13) \), we’ll obtain a set of solutions. Since the method of Lagrange multipliers yields only a necessary condition (but not a sufficient condition) for optimality in constriant problems, to obtain the optimal point, we still need a further test for each possible solution of \( (13) \). Thus, the last step is to stick \( x_1, …, x_n \) of each solution back into \( f(x_1, …, x_n) \), whichever gives the greatest value is the maximum

Summary

Optimization problems can be solved by three steps:

- define the Lagrangian \( \mathcal L(…) \)

- Solve \( \nabla\mathcal L(…)=0 \)

- Stick the solution of step2 back into the objective function

References

https://www.khanacademy.org/math/multivariable-calculus/applications-of-multivariable-derivatives/constrained-optimization/a/lagrange-multipliers-single-constraint

https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~elghaoui/Teaching/EE227A/lecture7.pdf

In the end

I’ve already lost the track of the resources I referred to when writing this blog. So~ thank all of them, especially the authors of The Elements of Statistical Learning, and this online course from MIT. I highly recommend this video, because it’s the very thing that motivates me to dig SVMs to the extent I’ve never imaged — otherwise, I may just learn the parameters and use it as a black box- -… If you have time to watch this course, may you find the motivation too :-)