Introduction

Part of the challenge of IRL is that IRL is an ill-defined problem, since there are 1) many optimal policies that can explain the demonstrations, and many rewards that can explain the optimal policy. MaxEnt IRL discussed in our previous posts handles the former ambiguity, but the later ambiguity is still unaddressed, meaning that IRL algorithms have difficulty distinguishing the true reward functions from those shaped by the environment dynamics. While shaped rewards can increase learning speed in the original training environment, when the reward is deployed at test-time on environments with varying dynamics, it may no longer produce optimal behaviors. In this post, we introduce adversarial inverse reinforcement learning (AIRL) that attempts to address this issue.

Preliminaries

In our previous post, we cast the MaxEnt IRL problem into a GAN optimization problem, and derive the optimal discriminator as

\[\begin{align} D(\tau)={\exp(f(\tau))\over\exp(f(\tau))+\pi(\tau)} \end{align}\]where \(f\) is the optimal reward function up to some constants as reward shaping does not affect the optimization problem. Note that we’ve folded \(Z\) into \(f\) as there is no way to uniquely learn \(Z\)(see this answer).

Learning from trajectories could be noisy due to the high variance. Therefore, we instead convert it into the single state and action case

\[\begin{align} D(s,a)={\exp(f(s,a))\over\exp(f(s,a))+\pi(a|s)}\tag 1 \end{align}\]Because, at optimality, \({1\over Z}\exp(f^*(s,a))\) is the optimal policy for the MaxEnt RL, \(f^*(s,a)=A^*(s,a)\) is the advantage function of the optimal policy.

The Reward Ambiguity Problem

Equation \((1)\) does not put any form of requirements on the reward function. As a result, there is no guarantee in \(f(s,a)\) to be the real reward function; \(f\) is free to be any shaped reward function since reward shaping preserves the optimal policy. Mathematically, \(f\) might learn to be any reward function of the following form

\[\begin{align} f(s,a,s')=r(s,a,s')+\gamma\Phi(s')-\Phi(s) \end{align}\]where \(\Phi:\mathcal S\rightarrow\mathbb R\) can be any function. Consequently, the reward function may not robust to changes in dynamics. Consider deterministic dynamics \(\mathcal T(s,a)\rightarrow s’\) and state-action rewards \(\hat r(s,a)=r(s,a)+\gamma\Phi(\mathcal T(s,a))-\Phi(s)\). It is easy to see that changing the dynamics \(\mathcal T\) to \(\mathcal T’\) such that \(\mathcal T’(s,a)\ne\mathcal T(s,a)\) means that \(\hat r(s,a)\) is no longer shaped in the same way as before.

Adversarial Inverse Reinforcement Learning

To address the reward ambiguity problem, AIRL employs an additional shaping term to mitigate the effects of unwanted shaping.

Formally, AIRL defines \(f\) as

\[\begin{align} f_{\psi,\phi}(s,a,s')=g_\psi(s)+\gamma h_\phi(s')-h_\phi(s) \end{align}\]where, ideally, \(g_\psi\) is optimized to be the ground truth reward function of the state plus some constant, \(h_\phi\) is optimized to be the optimal state value function plus some constant. As a shaping function, \(h_\phi\) helps mitigate the effects of unwanted shaping on the reward approximator \(g_\psi\).

Note that state only \(g_\psi(s)\) is important for learning a “disentangled” reward function, which is required for tasks where the dynamics model at test time differs from that at training time. On the other hand, when the dynamics model remains the same at test time, a state-action dependent \(g_\psi(s,a)\) performs better. This indicates that the practical application of AIRL may be limited as the “disentangled” reward function learned by state-only \(g_\psi(s)\) does not perform well. See Experimental Results for details

Reward Function

AIRL defines the negative of the generator loss as the policy objective, which gives the following reward function

\[\begin{align} r_{\psi,\phi}(s,a,s')=\log D_{\psi,\phi}(s,a,s')-\log(1-D_{\psi,\phi}(s,a,s')) \end{align}\]Losses

The discriminator loss is a binary classifier

\[\begin{align} \mathcal L_{D}(\psi, \phi)=\mathbb E_{\tau^E}[-\log D_{\psi, \phi}(x)]+\mathbb E_{\tau}[-\log(1-D_{\psi, \phi}(x))] \end{align}\]Algorithm

\[\begin{align} &\mathbf{AIRL:}\\\ &\quad \text{Initialize policy }\pi_\theta \text{ and discriminator } D_{\psi,\phi}\\\ &\quad \mathbf{For}\ i=1\text{ to }N:\\\ &\qquad \text{Collect trajectories }\tau_i\text{ by executing }\pi_\theta\\\ &\qquad \text{Obtain expert trajectories }\tau_i^E\\\ &\qquad \text{Train discriminator }D_{\psi,\phi}\text{ to classify }\mathcal \tau_i^E\text{ and }\tau_i\\\ &\qquad \text{Compute reward for state-actions in } \tau_i\\\ &\qquad \text{Update }\theta\text{ in policy }\pi_\theta\text{ using }\mathcal D_{samp} \end{align}\]where the reward function is the negative of the generator loss.

Training Details

IRL methods commonly learn rewards which explain behavior locally for the current policy, because the reward can ”forget” the signal that it gave to an earlier policy. This makes rewards obtained at the end of training difficult to optimize from scratch, as they overfit to samples from the current iteration. To somewhat mitigate this effect, we mix policy samples from the previous 20 iterations of training as negatives when training the discriminator.

Experimental Results

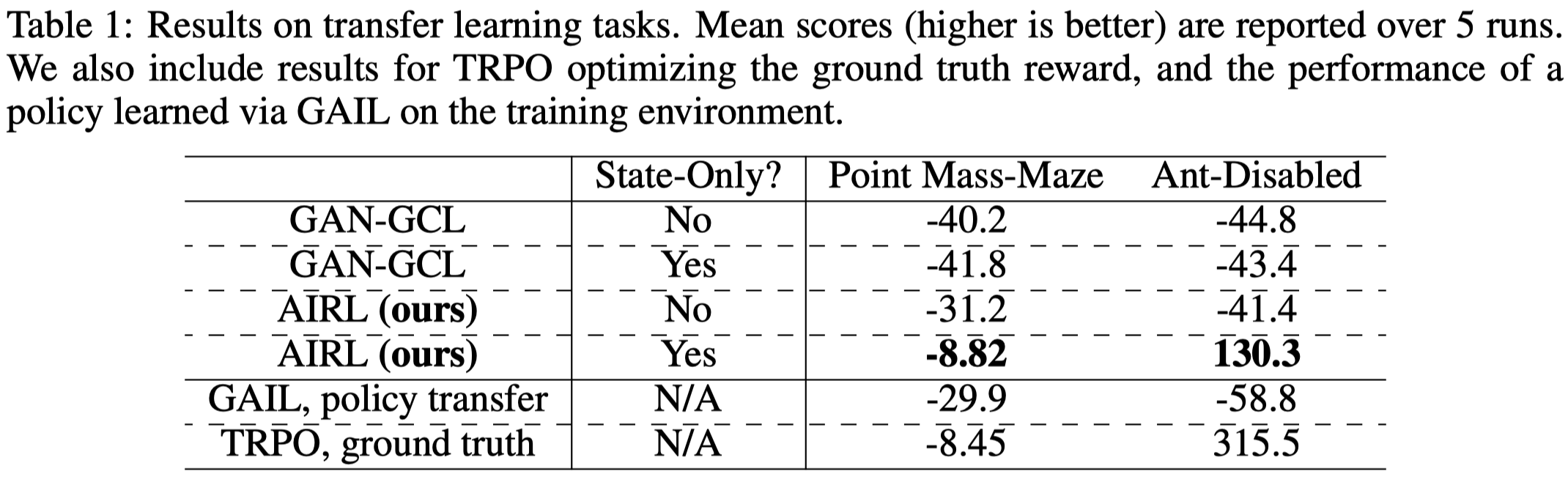

Figure1 shows that AIRL(state-only) is able to perform well in tasks where dynamics model is modified at test time—either the environment or the agent’s capability is changed, while other methods such as GAIL failed in these tasks.

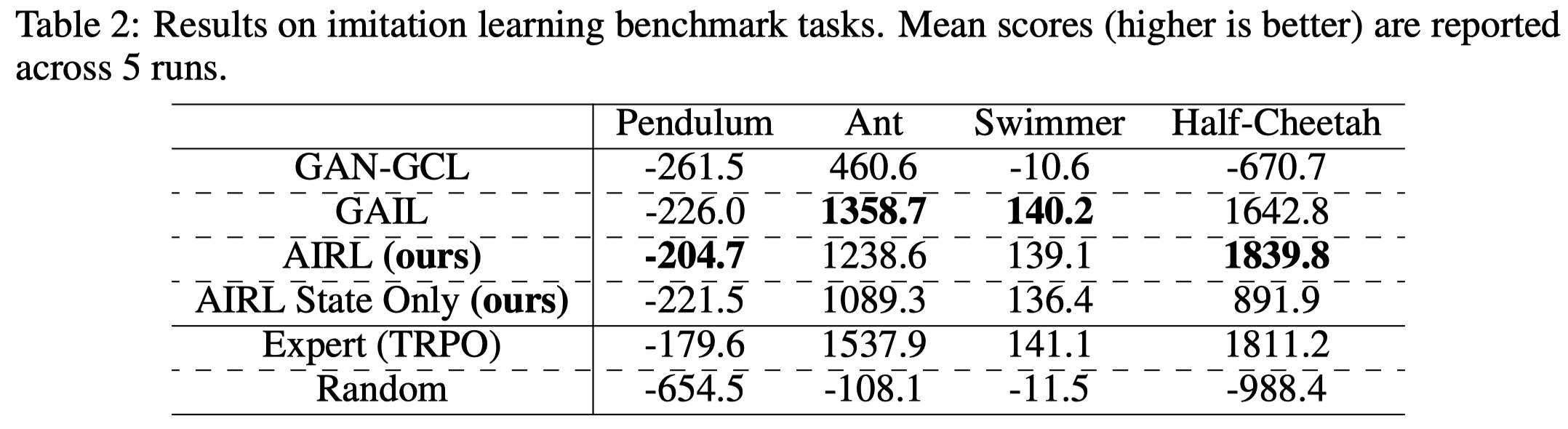

Figure 2 shows that AIRL(state-action) is able to recover the expert’s behavior. However, challenging tasks such as Humanoid are not tested. In light of recent application of imitation learning often uses GAIL, we assume AIRL may not work well for challenging tasks.

References

Justin Fu, Katie Luo, Sergey Levine. Learning Robust Rewards with Adversarial Inverse Reinforcement Learning