Introduction

Traditional reinforcement learning algorithms have achieved encouraging success in recent years. Their nature of reasoning on the atomic scale, however, makes them hard to scale to complex tasks. Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning(HRL) introduces high-level abstraction, whereby the agent is able to plan on different scales.

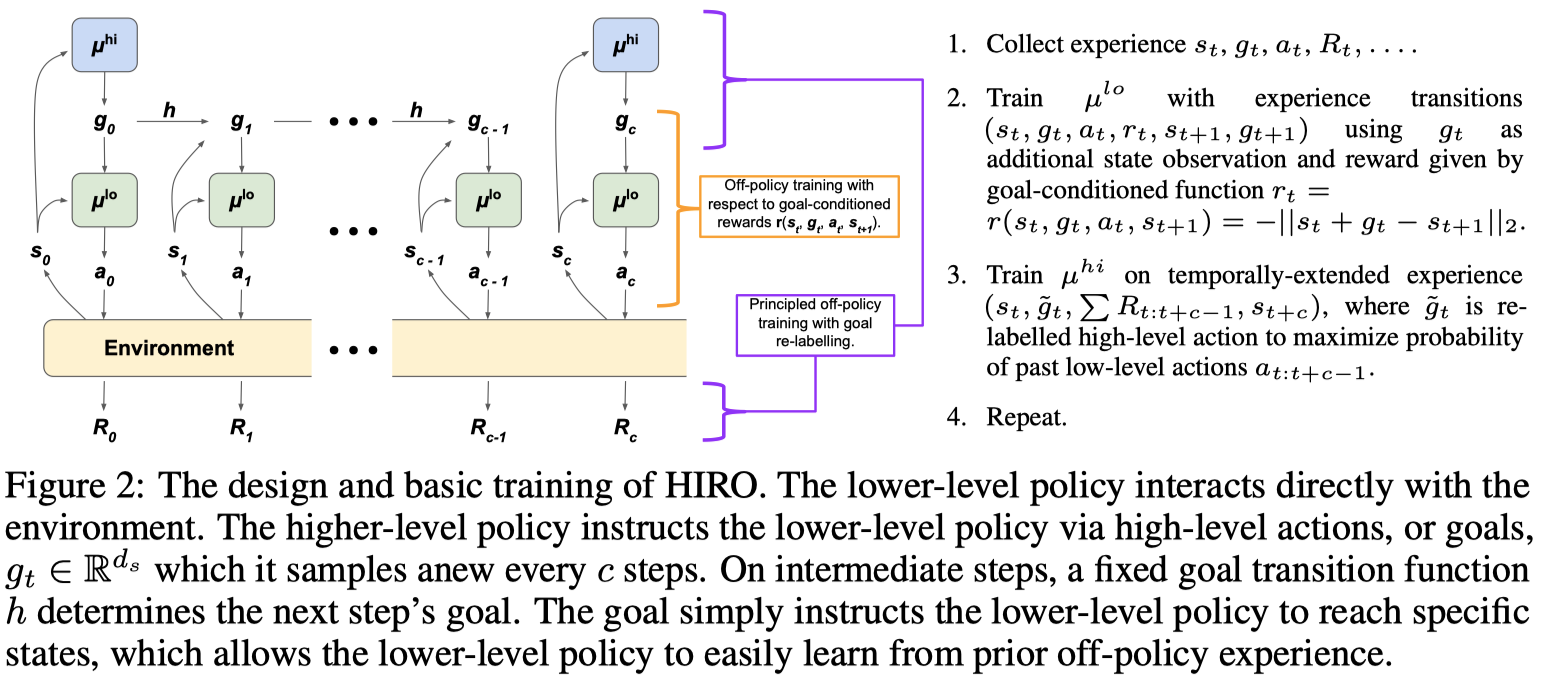

In this post, we discuss an HRL algorithm proposed by Ofir Nachum et al. 2018. The algorithm, known as HIerarchical Reinforcement learning with Off-policy correction(HIRO), is designed for goal-directed tasks, in which the agent tries to reach some goal state.

Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning with Off-Policy Correction

We first introduce three questions about Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning, HRL:

- How should one train the low-level policy to induce semantically distinct behavior?

- How should high-level policy actions be defined?

- How should multiple policies be trained without incurring an inordinate amount of experience collection?

HIerarchical Reinforcement learning with Off-policy correction(HIRO) can be well explained by answering the above questions(from here on, we only focus on a two-level HRL agent):

- In addition to state observations, we feed subgoals produced by the higher-level policy to lower-level policy so that the lower-level policy learns to exhibit different behavior for different goals it tries to achieve. Accordingly, to guide the learning process of the lower-level policy, we define the subgoal-conditioned reward function as

- The higher-level policy actions are defined to be subgoals, which the lower-level policy tries to achieve in a certain period of time. Subgoals are either sampled from the higher-level policy every \(c\) steps, \(g_t\sim\mu^{high}\), when \(t\equiv0\ (\mathrm{mod}\ c)\), or otherwise computed through a fixed goal transition function. Mathematically, a goal is defined as

- To improve data efficiency, we separately train high-level and low-level policies using an off-policy algorithm(e.g., TD3). Specifically, for a two-level HRL agent, the lower-level policy is trained with experience \((s_t, g_t, a_t, r_t, s_{t+1}, g_{t+1})\), where intrinsic reward \(r\) and goal \(g\) are computed by Eq.\((1)\) and Eq.\((2)\), respectively; the higher-level policy is trained on temporally-extended experience \((s_t, \tilde g_t, \sum R_{t:t+c-1}, s_{t+c})\), where \(\tilde g\) is the relabeled subgoal (which we will discuss in the next section), and \(R\) is the reward provided by the environment. Since all the additional variables are defined by the agent itself, experiences collected from the environment can be shared with both policies.

Goals in HIRO

The goal produced by the high-level policy describes the desired relative changes in state space. This makes sense of the definition of goal transition function defined in Eq.\((2)\), \(h(s_{t-1},g_{t-1},s_t)=s_t+g_t-s_{t-1}\), where \(s_t+g_t\) computes the desired state \(s_{t+c}\). It also brings a nice interpretation for the goal-conditioned reward function defined in Eq.\((1)\): the reward function simply penalizes according to the Euclidean distance between the desired state \(s_t+g_t\) and the next state \(s_{t+1}\) the agent reaches by taking action \(a_t\). Note that in this definition, goals are in the same form as the state observations.

So far, we have made sense of goals for the lower-level policy, now let us consider its role in the high-level policy. First, we notice that, although goals are produced by the high-level policy as high-level actions, they are in fact carried out by lower-level policy. As the lower-level policy evolves, the lower-level actions taken to achieve the same goal varies, which in turns results in different states and rewards collected along the way. This invalidates old high-level transitions \((s_t, g_t, \sum R_{t:t+c-1}, s_{t+c})\). To reinstate the experience, we relabel the goal such that it is likely to induce the same low-level behavior with the current instantiation of the lower-level policy. Mathematically, \(\tilde g_t\) is chosen to maximize the probability \(\mu^{low}(a_{t:t+c-1}\vert s_{t:t+c-1}, \tilde g_{t:t+c-1})\), where the intermediate goals \(\tilde g_{t+1:t+c-1}\) are computed using the goal transition function defined in Eq.\((2)\). In practice, we generally instead maximize the log probability \(\log\mu^{low}(a_{t:t+c-1}\vert s_{t:t+c-1}, \tilde g_{t:t+c-1})\), which could be computed as follows if the action is sampled from a Gaussian distribution

\[\begin{align} \log\mu^{low}(a_{t:t+c-1}|s_{t:t+c-1}, \tilde g_{t:t+c-1})\propto-{1\over2}\sum_{i=t}^{t+c-1}\Vert a_i-\mu^{low}(s_i,\tilde g_i)\Vert_2^2+constant\tag {3} \end{align}\]To approximately maximize this quantity, we compute this log probability for a number of goals \(\tilde g_t\), and choose the maximal goal to relabel the experience. For example, we calculate this quantity on eight candidate goals sampled randomly from Gaussian distribution centered at \(s_{t+c}-s_t\), also including the original goal \(g_t\) and a goal corresponding to the difference \(s_{t+c}-s_t\) in the candidate set, to have a total of 10 candidates. The one maximizing Eq.\((3)\) is therefore chosen to be the relabeled goal.

Algorithm

The following figure excerpted from the paper perfectly elucidates the algorithm, where both high-level and low-level policies are trained by TD3.

Discussion

Wait, what on earth guarantees the goal to be the desired relative changes in state space?

It seems that the guarantee is only carried out by the goal transition model \(h\) defined in Eq.\((2)\) and low-level reward \(r\) defined in Eq.\((1)\). However, there seems no guarantee from the high-level policy which is exactly the part producing the goal! No idea if this will be an issue.

References

Ofir Nachum et al. Data-Efficient Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning

Scott Fujimoto et al. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods