Introduction

For problems with sparse rewards and long time horizons, two common strategies to improve sample efficiency are: 1. do imitation learning, 2. exploit the hierarchical structure of the problem. Le et al. 2018 proposed an algorithmic framework called hierarchical guidance, which leverages hierarchical structure in imitation learning. In this framework, the high-level expert guides the low-level learner such that low-level learning only occurs when necessary and only over relevant parts of the state space. Such attention to relevant parts of the state space speeds up learning (improves sample efficiency) while omitting feedback on the already mastered subtasks reduce expert effort (improve label efficiency).

Preliminaries

In this section, we briefly introduce the necessary concepts and notions used in the rest of the post.

We first introduce the general hierarchical formalism. A hierarchical agent simultaneously learns a high-level policy \(\pi^{high}: \mathcal S\rightarrow\mathcal G\), aka, meta-controller, as well as a low-level policy \(\pi^{low}:\mathcal S\times \mathcal G\rightarrow\mathcal A\), aka, subpolicies. For each goal \(g\in\mathcal G\), we have a (possible learned) termination function \(\beta:\mathcal S\times \mathcal G\rightarrow{True,False}\), which terminates the execution of \(\pi^{low}\). The agent behaves as follows

\[\begin{align} &\mathbf{for}\ t^{h}=1\dots T^{high}\ \mathbf{do}\\\ &\quad\mathrm{observe\ state\ }s\ \mathrm{and\ choose\ goal\ }g\leftarrow\pi^{high}(s)\\\ &\quad\mathbf{for}\ t^{l}=1\dots t^{low}\ \mathbf{do}\\\ &\quad\quad\mathrm{observe\ state\ }s\\\ &\quad\quad\mathbf{if}\ \beta(s,g)\ \mathbf{then\ break}\\\ &\quad\quad\mathrm{choose\ action\ }a\leftarrow\pi^{low}(s,g) \end{align}\]We further denote a high-level trajectory as \(\tau_{HI}=(s_1,g_1,s_2,g_2,\dots)\), a low-level trajectory as \(\tau=(s_1, a_1,s_2,a_2\dots)\). Rewards may be included in low-level trajectories depending on whether the low-level policy is learned through imitation learning or reinforcement learning. The full trajectory and overall hierarchical trajectory are denoted as \(\tau_{FULL}=(s_1,a_1,s_2,a_2\dots)\) and \(\sigma=(s_1,g_1,\tau_1,s_2,g_2,\tau_2,\dots)\), respectively.

We then assume an expert provides one or several types of supervision:

- \(\mathrm{HierDemo}(s)\): generates hierarchical demonstration \(\sigma^*=(s_1^*,g_1^*,\tau_1^*,s_2^*,g_2^*,\tau_2^*\dots)\)

- \(\mathrm{Label}{HI}(\tau{HI})\): labels a high-level trajectory \(\tau_{HI}\), yielding a labeled data set \({(s_1,g^*_1),(s_2,g^*_2),\dots}\)

- \(\mathrm{Label}_{LO}(\tau;g)\): labels a low-level trajectory \(\tau\), yielding a labeled data set \({(s_1,a_1^*),(s_2,a_2^*),\dots}\). If the agent also learns terminal functions \(\beta\), the resulting data set becomes \({(s_1,a_1^*,w_1^*),(s_2,a_2^*,w_2^*),\dots}\), where \(w^*\in{True,False}\).

- \(\mathrm{Label}{FULL}(\tau{FULL})\): labels a full trajectory \(\tau_{FULL}=(s_1,a_1,s_2,a_2\dots)\), yielding a labeled data set \({(s_1,a^*_1),(s_2,a^*_2),\dots}\)

- \(\mathrm{Inspect}_{LO}(\tau;g)\): verifies whether a goal \(g\) was accomplished, returning either Pass or Fail

- \(\mathrm{Inspect}{FULL}(\tau{FULL})\): verifies whether the overall goal was accomplished, returning either Pass or Fail

In the rest of the post, we will discuss three algorithms proposed by Le et al.

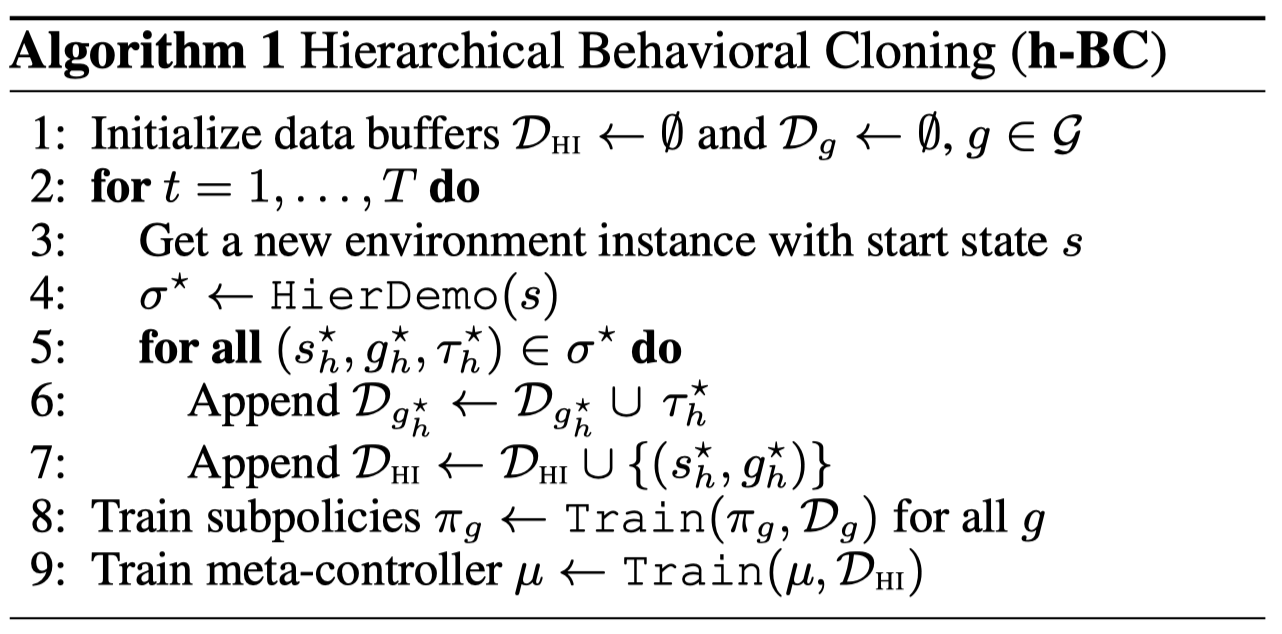

Hierarchical Behavior Cloning

This algorithm is simple — it is basically imitation learning in a two-level hierarchical structure. However, it typically suffers the mismatch between the expert’s state-action distribution and the learner’s distribution.

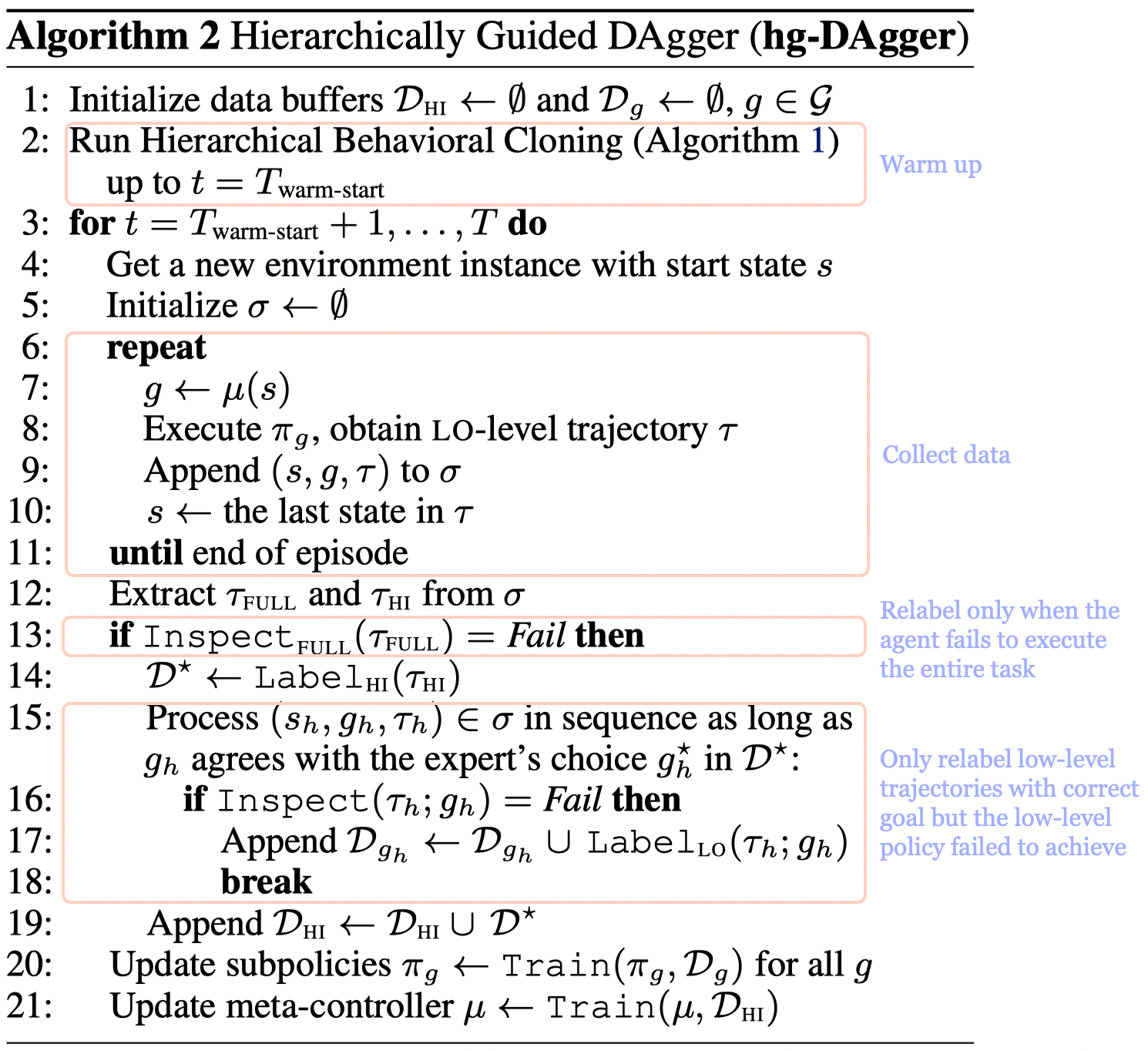

Hierarchically Guided DAgger

The logic behind adding data to imitation buffer is: we only relabel those trajectories that have the correct goal but the policy fails to achieve it. This makes sense, since it is fruitless to correct the actions if the goal is itself wrong in the first place.

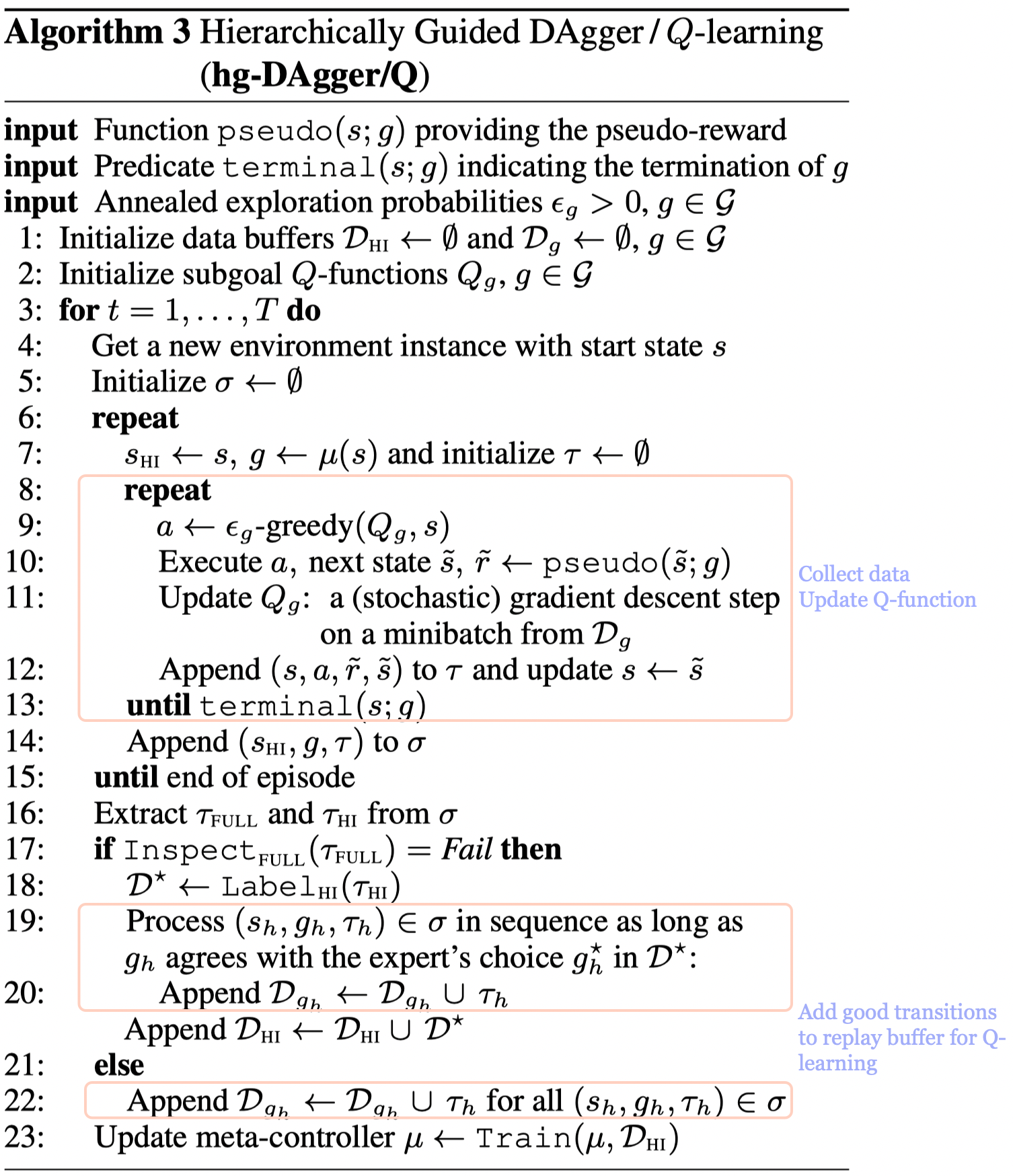

Hierarchically Guided Dagger/Q-Learning

where the pseudo-reward is defined to be

\[\begin{align} pseudo(s,g)=\begin{cases} 1&&\mathrm{if\ success}(s;g)\\\ -1&&\mathrm{if\ \neg success}(s;g)\ \mathrm{and\ terminal()}\\\ -\kappa&&\mathrm{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align}\]where \(\kappa>0\) is a small penalty to encourage short trajectories. The predicates \(\mathrm{success}\) and \(\mathrm{terminal}\) are provided by an expert or learned from supervised or reinforcement feedback.

In contrast to hierarchically guided DAgger, in which we do imitation learning when the goal is met but not achieved, here we use whatever experience confirmed valuable to do reinforcement learning. Notice that the good transitions to reinforcement learning are defined to be those whose goal agrees with the expert’s choice \(g_h^*\), regardless of whether the low-level trajectory achieves these goals or not. As in regular reinforcement learning algorithms, these transitions, which do not achieve any goals, also help the algorithm to learn the environment.

Discussion

Hierarchical guidance has some pros and cons.

Pros:

- It is particularly suitable in settings where we have access to high-level semantic knowledge, the subtask horizon is sufficiently short, but the low-level expert is too costly or unavailable.

Cons:

- Goals and goal detectors are generally manually designed specifically to environment. It may be challenging to design one for some environments. For Montezuma’s, the authors simply propose to count the change of pixel inside a pre-specified box(subgoal box) as goal detector.

References

Le, Hoang M., Nan Jiang, Alekh Agarwal, Miroslav Dudík, Yisong Yue, and Hal Daumé. 2018. “Hierarchical Imitation and Reinforcement Learning.” 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2018 7: 4560–73.