Introduction

So far we have discussed RL algorithms across many fields, but all of these methods focus on a single agent. These methods may not generalize well to multi-agent environments, since they do not explicitly represent interaction between the agents. Worse still, these methods may not even converge since each agent’s policy is changing as training progresses, and the environment becomes non-stationary from the perspective of any individual agent. This presents learning stability challenges and prevents the straightforward use of past experience replay, which is crucial for stabilizing deep Q-learning. Policy gradient methods, on the other hand, usually exhibit very high variance when coordination of multiple agents is required.

In this post, we introduce an algorithm named Multi-Agent-Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient(MADDPG), proposed by Lowe et al. 2018. In a nutshell, this algorithm follows the pattern of DDPG, but uses a centralized action value function \(Q_i(s, a_1, \dots, a_N)\) that takes as input the actions of all agents \(a_1, \dots, a_N\), in addition to some state information \(s\), and outputs the \(Q\)-value for agent \(i\).

Multi-Agent Deep Determinisitc Policy Gradient

Developing History

The authors tried to develop a general-purpose multi-agent learning algorithm that 1) leads to a learned policy that only use local information at execution time, 2) does not assume a differentiable model of environment dynamics or any particular structure on the communication method between agents, and 3) is applicable not only to cooperative interaction but to competitive or mixed interaction involving both physical and communicative behavior. As a result, they adopted the framework of centralized training with decentralized execution, which allows the policies to use extra information to ease training. This rules out general \(Q\)-learning as the \(Q\)-function generally cannot contain different information at training and test time. Motivated by the observation that if we know the actions taken by all agents, the environment is stationary even as the policies changes(i.e., \(P(s’\vert s,a_1,\dots,a_N,\pi_1,\dots,\pi_N)=P(s’\vert s,a_1,\dots,a_N)=P(s’\vert s,a_1,\dots,a_N,\pi_1’,\dots,\pi_N’)\) for any \(\pi_i\ne \pi_i’\)), they proposed a simple extension of actor-critic policy gradient methods where the critic is augmented with extra information about the policies of other agents. To improve sample efficiency, they further extended the above idea to work with deterministic policies, resulting in a DDPG-style algorithm we will discuss next.

Algorithm

Consider a game with \(N\) agents, each with a policy \(\mu_i\) and a centralized action-value function \(Q_i(s,a_1,\dots,a_N)\) parametrized by \(\theta_i\). The policy gradient and the loss of the centralized action-value function can be written as

\[\begin{align} \nabla_{\theta_i}J(\mu_i)&=\mathbb E_{s,a\sim\mathcal D}\left[\nabla_{\theta_i}\mu_i(s_i)\nabla_{a_i}Q_i(s,a_1,\dots,a_N)|_{a_i=\mu_i(s_i)}\right]\\\ \mathcal L(\theta_i)&=\mathbb E_{s, a, r, s'\sim\mathcal D} \left[(y_i-Q_i(s,a_1,\dots,a_N))^2\right]\\\ where\quad y_i&=r_i+\gamma Q_i'(s',a_1',\dots,a_N')|_{a_i=\mu_i(s'_i)} \end{align}\]Here the experience replay buffer \(\mathcal D\) contains the tuples \((s,s_1,\dots,s_N,s’,a_1,\dots,a_N,r_1,\dots,r_N)\), recording experiences of all agents. These are essentially the objectives in DDPG augmented by a centralized action-value function. Notice that although the centralized action-value function is specialized to each agent, by taking as inputs all other actions, it forces the agent to take into account of the actions of other agents, which significantly helps in cooperation and communication.

One downside of centrailized \(Q\)-function is that the input space of \(Q\)-function grows linearly with the number of agents \(N\). The authors suggest that this could be remedied in practice by, for example, having a modular \(Q\)-function that only consider agents in a certain neighborhood of a given agent.

Inferring Policies of Other Agents

Notice that the target action value \(y_i\) requires the knowledge of other agents’ policy to compute all \(a’\)s. This is not a particular restrictive assumption; if our goal is to train agents to exhibit complex communicative behavior in simulation, this information is often available to all agents. However, we can relax this assumption by having each agent \(i\) maintain an approximation \(\hat \mu_i^j\) to the true policy of agent \(j\), \(\mu_j\). This approximate policy is learned by maximizing the log probability of agent \(j\)’s actions, with an entropy regularizer:

\[\begin{align} \mathcal L(\phi_i^j)=-\mathbb E\left[\log\hat u_i^j(a_j|s_j)+\lambda\mathcal H(\hat\mu_i^j)\right] \end{align}\]Then we use their target networks \(\hat \mu_i’^j\) to generate \(a’_j\) for the target action value.

Caveat: There is a confusing statement in the paper

we input the action log probabilities of each agent directly into \(Q\), rather than sampling.

This is different from their associated code, which uses sampling actions as inputs to the \(Q\) function.

Policy Ensembles

The authors also proposed to use policy ensembles to avoid policy overfitting their competitors. Specifically, for each agent, we maintain a collection of \(K\) sub-policies. At the beginning of each episode, we randomly select one particular sub-policy for each agent to execute. Noticeably, replay buffers are used for each sub-policy of each agent. This may reduce the variance introduced by the off-policy data, but it significantly increases the memory requirement.

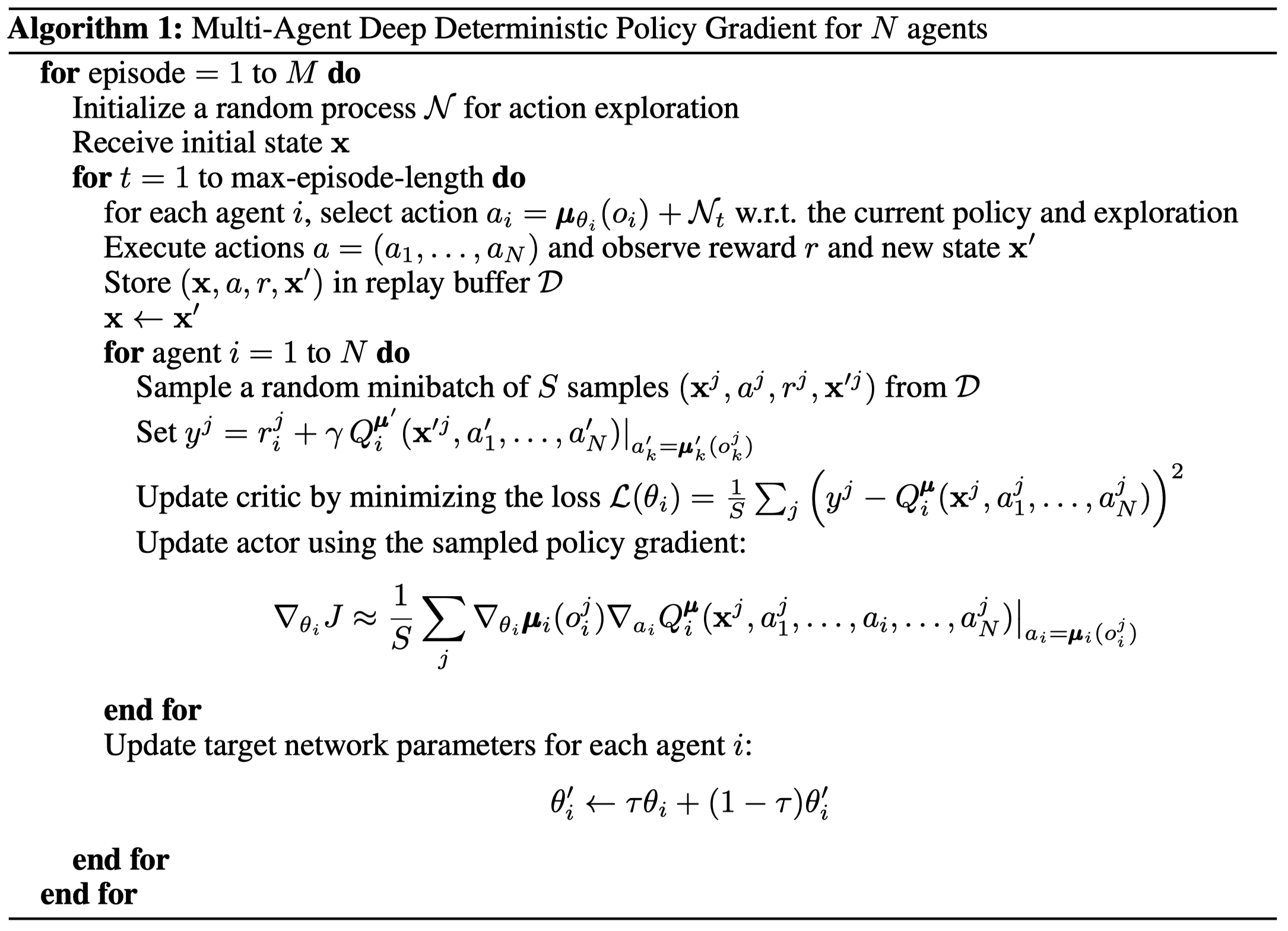

Pseudocode

This pseudocode does not take into account the policy approximation and policy ensembles. As we mentioned before, it’s basically DDPG with an augmented \(Q\)-function.

Experimental Results

References

OpenAI Learning to Cooperate, Complete, and Communicate

Lowe, Ryan, Yi Wu, Aviv Tamar, Jean Harb, Pieter Abbeel, and Igor Mordatch. 2019. “Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed Cooperative-Competitive Environments,” 6380–91.