Introduction

We distill some valuable contents of “A Survey and Critique of Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning”, proposed by Pablo et al. 2019, and highlight some interesting papers it refers to for future reading. Noticeably, this post does not intend to address any algorithms but serves as a literature reference in the field of multiagent reinforcement learning.

We refer to multiagent (deep) reinforcement learning as MARL instead of MDRL used by the authors.

Reinforcement Learning(Section 2)

We first refresh our memory on some typical RL algorithms and enumerate some concerns and potential solutions.

Policy gradient methods can have high variance and often converge to local optima. The former is further exacerbated in MARL as all agents’ rewards depend on the rest of the agents, and as the number of agents increase, the probability of taking a correct gradient direction decreases exponentially. COMA [4] and MADDPG [3] addressed this high variance via a central critic.

Function approximation, bootstrapping, and off-policy learning are considered the three main properties that, when combined, can make the learning to diverge and are known as the deadly triad[2]. Recently, some works have shown that non-linear function approximators poorly estimates the value function [5, 6, 7] and another work found problems with Q-learning using function approximation (over/under-estimation, instability and even divergence) due to the delusional bias; delusional bias occurs whenever a backed-up value estimate is derived from action choices that are not realizable in the underlying policy class[8].

Experience replay was first introduced by Mnih et al. in DQN to stabilize the learning process by breaking the correlation between samples. Recent works are designed to reduce the problem of catastrophic forgetting (this occurs when the trained neural network performs poorly on previously learned tasks due to a non-stationary training distribution) and the ER buffer, in DRL [9] and MARL [10]

Convergence Results of MARL(Section 3.1)

Littman[11] studied convergence properties of reinforcement learning joint action agents in Markov games with the following conclusion: in adversarial environments (zero-sum games) an optimal play can be guaranteed against an arbitrary opponent. In coordination environments, strong assumptions need be made about other agents to guarantee convergence of optimal behavior. In other types of environments no value-based RL algorithms with guaranteed convergence properties are known.

Srinivasan et al.[12] showed a connection between update rules for actor-critic algorithms for multi-agent partially observable settings and (counterfactual) regret minimization(regret is defined as the opportunity loss between the optimal and actual reward, i.e. \(R=\mathbb E[V^*-Q(a)]\), where \(V^*\) is the maximum reward): The advantage values are scaled counterfactual regrets. This leads to new convergence properties of independent RL algorithms in zero-sum games with imperfect information.

Challenges of Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning

The challenges presented by MARL include:

- Catastrophic forgetting: an agent performs well against the current opponents may no long be able to defeat the previous version of opponents.

- Non-stationary environment: The opponents’ or teammates’ joint policy evolves as they learn, which render the environment non-stationary.

- Curse of dimensionality: The dimensionality of the joint policy grows exponentially as the number of agents increases

- Multi-agent credit assignment: The credit assignment problem becomes increasingly harder with multiple agents. See this post from BAIR for an example

- Global exploration

- Relative overgeneralization: Relative overgeneralization occurs when a suboptimal Nash Equilibrium in the joint space of actions is preferred over an optimal one because each agent’s action in the suboptimal equilibrium is a better choice on average when matched with arbitrary explorative actions from collaborating agents.

We select several recent papers related to the problems in MAL :

- Evolutionary dynamics of multiagent learning: Bloembergen et al Evolutionary Dynamics of Multi-Agent Learning: A Survey

- Learning in non-stationary environments: Hernandez-Leal et al. A Survey of Learning in Multiagent Environments: Dealing with Non-Stationarity

- Agents modeling agents: Albrecht et al. Autonomous agents modelling other agents: A comprehensive survey and open problems

- Transfer learning in Multiagent RL: Silva et al. A survey on transfer learning for multiagent reinforcement learning systems

You may find more from the end of the Section 3.1 in the paper.

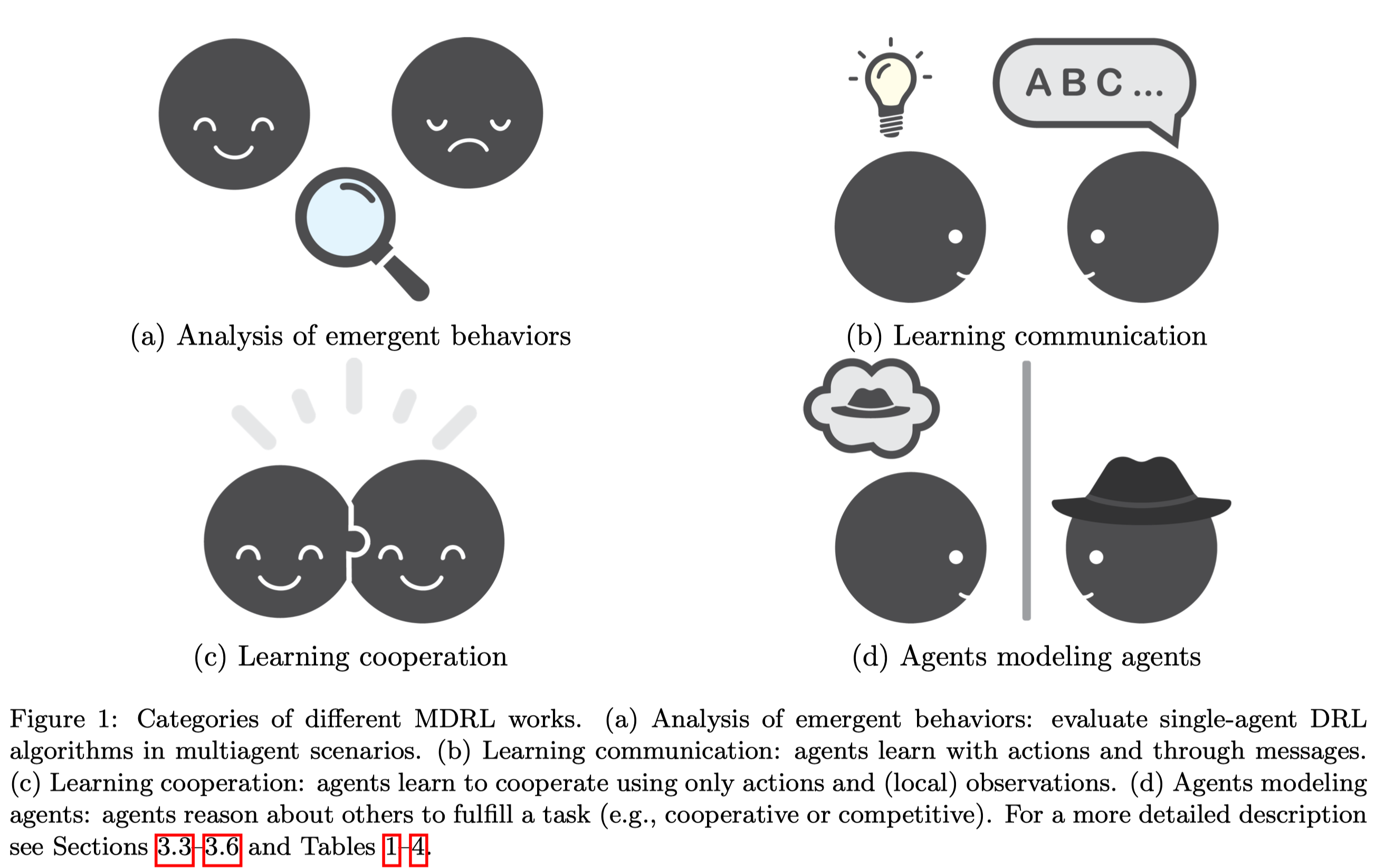

Categories of Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning

The authors groups MARL into four categories:

- Analysis of emergent behaviors: evaluate single-agent DRL algorithms in multiagent scenarios.

- Learning communication: agents learn communication protocols to solve cooperative tasks

- Learning cooperation: agents learn to cooperate using only actions and (local) observations

- Agents modeling agents: agents reason about others to fulfill a task (e.g., best response learners)

We briefly discuss each category in the rest of this section.

Emergent Behaviors

Self-play(Fictitious play) is a useful concept for learning algorithms since it can guarantee convergence under certain constraints, e.g, two-player zero-sum games. Despite its common usage self-play can be brittle to forgetting past knowledge[13]. To overcome this issue, Leibo et al.[14] proposed Malthusian reinforcement learning as an extension of self-play to population dynamics. The approach can be thought of as community coevolution and has been shown to produce better results (avoiding local optima) than independent agents with intrinsic motivation.

Bansal et al.[15] studied PPO in multi-agent setting. They adopted two techniques to deal with multi-agent difficulties: exploration rewards and opponent sampling which maintains a pool of older version of the opponent to sample from, in contrast to using the most recent version.

Lazaridou et al.[16] and Mordatch and Abbeel[17] studied the emergence of language in multi-agent setting.

Learning Communications

Pesce et al. proposed Memory-Driven MADDPG[18], in which the agents use a shared memory as a communication channel: before taking an action, the agent first reads the memory, then writes a response. Experimental results highlighted the fact that the communication channel was used differently in different environments, e.g., in simpler tasks, agents significantly decrease their memory activity near the end of the task as there are no more changes in the environment; in more complex environments, the changes in memory usage appear at a much higher frequency due to the presence of many sub-tasks

Kim et al.[19] proposed Message-Dropout MADDPG, in which messages are randomly dropped out at training time following the similar idea of dropout in deep learning.

Lowe et al.[20] discussed common pitfalls(and recommendations to avoid those) while measuring communication in multiagent environments.

Learning Cooperation

The experience replay used in DRL fails to work in MARL since the dynamics in MARL changes over time, making the experience obsolete. Foerster et al.[21] alleviated this problem by adding additional information to the experience tuple that can help to disambiguate the age of the sampled data from the replay memory. Two approaches were proposed. The first is multiagent importance sampling which adds the probability of the joint action. The second is multiagent fingerprints which adds the estimate of other agents’ policyies, e.g., training iteration number and exploration rate as the fingerprint.

LDQN[22] took the leniency concept to overcome relative overgeneralization. Lenient learners initially maintains an optimistic disposition to mitigate the noise from transitions resulting in miscoordination, preventing agents from being drawn towards sub-optimal but wide peaks in the reward search space. Similar to previous methods, LDQN combats the experence replay problem by adding leniency value to the experience tuple; if this value does not meet some condition, the tuple is ignored.

DEC-HDRQNs[23] took the similar motivation to LDQN, making an optimistic value update. The experience replay in DEC-HDRQNs is extended into concurrent experience replay trajectories, which are composed of three dimensions: agent index, the episode, and the timestep; when training, the sampled trace have the same starting timesteps.

Lowe et al. noted that using standard policy gradient methods on multiagent environments yields high variance and performs poorly. This occurs because the variance is further increased as all the agents’ rewards depend on the rest of the agents, and it is formally shown that as the number of agents increases, the probability of taking a correct gradient direction decreases exponentially. As a result, they proposed MADDPG to train a centralized critic per agent with all agents’ policy as input.

COMA[24] was designed for the fully centralized setting and the multiagent credit assignment problem. They compute a counterfactual baseline that marginalizes out the action of the agent while keeping the rest of the other agents’ actions fixed. This counterfactual baseline has its roots in difference rewards, which is a method for obtaining the individual contribution of an agent in a cooperative multiagent team. In particular, the aristocrat utility aims to measure the difference between an agent’s actual action and the average action. The intention would be equivalent to sideline the agent by having the agent perform an action where the reward does not depend on the agent’s actions, i.e., to consider the reward that would have arisen assuming a world without that agent having ever existed.

QMIX[25] relies on the idea of factorizing value function, assuming a mixing network that combines the local values in a non-linear way, which can represent monotonic action-value functions. Factorization of value functions in multiagent scenarios is an ongoing research topic, with open questions such as how well factorizations capture complex coordination problems and how to learn those factorization[26]

Agents Modeling Agents

DPIQN and DPIRQN[27] learn other agents’ policy features with recourse to auxiliary tasks. The auxiliary task modifies the loss function by computing an auxiliary loss: the cross entropy loss between the inferred others’ policy and the ground truth(one-hot action vector) of the others. Then, the Q value function of the learning agent is conditioned on the opponent’s policy features, which aims to reduce the non-stationarity of the environment.

SOM[28] tries to infer other agents’ goals instead of modeling their policy. It is expected to work best when agents share a set of goals from which each agent gets assigned one at the beginning of the episode and the reward structure depends on both of their assigned goals.

NFSP[29] and its generalization PSRO[30] build on fictitious self-play. These methods works well in partially observable games because imperfect-information games generally require stochastic strategies to achieve optimal behavior. Compare to DQN, their experience varies more smoothly, resulting in a more stable data distribution, more stable neural networks and better performance.

M3DDPG[31] extends the MADDPG with the minimax idea, which updates policies considering a worst-case scenario: assuming that all other agents act adversarially. To make the minimax learning objective computational tractable, M3DDPG takes ideas from robust reinforcement learning which implicitly adopts the minimax idea by using the worst noise concept.

LOLA[32] accounts for anticipated learning of the other agents by optimizing the expected return after the opponent updates its policy one step. Therefore, a LOLA agent must have access to other agents’ policy and it directly shapes the policy updates of other agents to maximize its own reward.

Deep BPR+ uses the environment reward and the online learned opponent model to construct a rectified belief over the opponent strategy. Additionally, it leverage ideas from policy distillation and extends them to the multiagent case to create a distilled policy network. In this case, whenever a new acting policy is learned, distillation is applied to consolidate the new updated library which improves in terms of storage and generalization.

References

- Pablo Hernandez-Leal, Bilal Kartal, and Matthew E. Taylor. 2019. “A Survey and Critique of Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning.” Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 33 (6): 750–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10458-019-09421-1.

- R. S. Sutton, A. G. Barto. Reinforcement Learning: An introduction, 2nd Edition, MIT Press, 2018

- R. Lowe, Y. Wu, A. Tamar, J. Harb, P. Abbeel, I. Mordatch, Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed CooperativeCompetitive Environments., in: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017,

- J. N. Foerster, R. Y. Chen, M. Al-Shedivat, S. Whiteson, P. Abbeel, I. Mordatch, Learning with OpponentLearning Awareness., in: Proceedings of 17th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

- A. Ilyas, L. Engstrom, S. Santurkar, D. Tsipras, F. Janoos, L. Rudolph, A. Madry, Are deep policy gradient algorithms truly policy gradient algorithms?, CoRR

- S. Fujimoto, H. van Hoof, D. Meger, Addressing function approximation error in actor-critic methods, in: International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018.

- G. Tucker, S. Bhupatiraju, S. Gu, R. E. Turner, Z. Ghahramani, S. Levine, The mirage of action-dependent baselines in reinforcement learning, in: International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018.

- T. Lu, D. Schuurmans, C. Boutilier, Non-delusional Q-learning and value-iteration, in: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018

- D. Isele, A. Cosgun, Selective experience replay for lifelong learning, in: Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- G. Palmer, R. Savani, K. Tuyls, Negative update intervals in deep multi-agent reinforcement learning, in: 18th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 2019.

- M. L. Littman, Value-function reinforcement learning in Markov games, Cognitive Systems Research 2 (1) (2001) 55–66.

- S. Srinivasan, M. Lanctot, V. Zambaldi, J. P´erolat, K. Tuyls, R. Munos, M. Bowling, Actor-critic policy optimization in partially observable multiagent environments, in: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018, pp. 3422–3435.

- J. Z. Leibo, E. Hughes, M. Lanctot, T. Graepel, Autocurricula and the emergence of innovation from social interaction: A manifesto for multi-agent intelligence research, CoRR 2019

- J. Z. Leibo, J. Perolat, E. Hughes, S. Wheelwright, A. H. Marblestone, E. Duenez-Guzman, P. Sunehag, I. Dunning, T. Graepel, Malthusian reinforcement learning, in: 18th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 2019.

- T. Bansal, J. Pachocki, S. Sidor, I. Sutskever, I. Mordatch, Emergent Complexity via Multi-Agent Competition., in: International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018.

- A. Lazaridou, A. Peysakhovich, M. Baroni, Multi-Agent Cooperation and the Emergence of (Natural) Language, in: International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017.

- I. Mordatch, P. Abbeel, Emergence of grounded compositional language in multi-agent populations, in: Thirty Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- E. Pesce, G. Montana, Improving coordination in multi-agent deep reinforcement learning through memorydriven communication, CoRR, 2019

- W. Kim, M. Cho, Y. Sung, Message-Dropout: An Efficient Training Method for Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning, in: 33rd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2019.

- R. Lowe, J. Foerster, Y.-L. Boureau, J. Pineau, Y. Dauphin, On the pitfalls of measuring emergent communication, in: 18th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 2019.

- J. N. Foerster, N. Nardelli, G. Farquhar, T. Afouras, P. H. S. Torr, P. Kohli, S. Whiteson, Stabilising Experience Replay for Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning., in: International Conference on Machine Learning, 2017.

- G. Palmer, K. Tuyls, D. Bloembergen, R. Savani, Lenient Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning., in: International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 2018.

- S. Omidshafiei, J. Pazis, C. Amato, J. P. How, J. Vian, Deep Decentralized Multi-task Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning under Partial Observability, in: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, 2017.

- J. N. Foerster, G. Farquhar, T. Afouras, N. Nardelli, S. Whiteson, Counterfactual Multi-Agent Policy Gradients., in: 32nd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2017.

- T. Rashid, M. Samvelyan, C. S. de Witt, G. Farquhar, J. N. Foerster, S. Whiteson, QMIX - Monotonic Value Function Factorisation for Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning., in: International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018.

- J. Castellini, F. A. Oliehoek, R. Savani, S. Whiteson, The Representational Capacity of Action-Value Networks for Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning, in: 18th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 2019.

- Z.-W. Hong, S.-Y. Su, T.-Y. Shann, Y.-H. Chang, C.-Y. Lee, A Deep Policy Inference Q-Network for MultiAgent Systems, in: International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 2018.

- R. Raileanu, E. Denton, A. Szlam, R. Fergus, Modeling Others using Oneself in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning., in: International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018.

- J. Heinrich, D. Silver, Deep Reinforcement Learning from Self-Play in Imperfect-Information Games.

- M. Lanctot, V. F. Zambaldi, A. Gruslys, A. Lazaridou, K. Tuyls, J. P´erolat, D. Silver, T. Graepel, A Unified Game-Theoretic Approach to Multiagent Reinforcement Learning., in: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017.