Introduction

We discuss an agent, namely Never Give Up(NGU) proposed by Badia et al. 2020 at DeepMind., that achieves state-of-the-art performance in hard exploration games in Atari without any prior knowledge while maintaining a very high score across the remaining games. In order to achieve effective exploration, the NGU agent uses a combination of episodic and life-long novelties. To retain the high performance on dense reward environments, the NGU agent uses a Universal Value Function Approximator(UVFA) to interpolate exploration and exploitation.

Intrinsic Rewards

Limitations of Previous Intrinsic Reward Methods

It is known that naive exploration methods, such as epsilon-greedy policy, can easily fail in sparse reward settings, which often require courses of actions that extend far into the future. Many intrinsic reward methods have been proposed lately to drive exploration. One type is based on the idea of state novelty which quantifies how different the current state is from those already visited (see examples from our previous post). The problem is that these exploration bonus fades away when the agent becomes familiar with the environment. This discourages any future visitation to states once their novelty vanished, regardless of the downstream learning opportunities it might allow. The other type of intrinsic reward is built upon the prediction error, e.g., ICM and RND. However, building a predictive model from observations is often expensive, error-prone, and can be difficult to generalize to arbitrary environments. In the absence of the novelty signal, these algorithms reduce to undirected exploration schemes. Therefore, a careful calibration between the speed of the learning algorithm and that of the vanishing rewards is often required.

The Never-Give-Up Intrinsic Reward

Puigdomènech Badia et al. propose an intrinsic reward method that takes into account both episodic and life-long novelties as follows

\[\begin{align} r^i_t=r^{episode}_t\cdot\min\{\max\{\alpha_t,1\},L\} \end{align}\]where the life-long novelty \(\alpha_t\) could be interpreted as a modulator that controls the scale of the episodic intrinsic reward \(r^{episode}_t\). \(L=5\) is a chosen maximum reward scaling.

Before we delve into details, let’s explain a bit the purposes of these two novelties. The episodic novelty encourages visits to states that distinct from the previous states but rapidly discourages revisiting the same state within the same episode. On the other hand, the life-long novelty regulates the episodic novelty by slowly discouraging visits to states visited many times across episodes.

Episodic Novelty Module

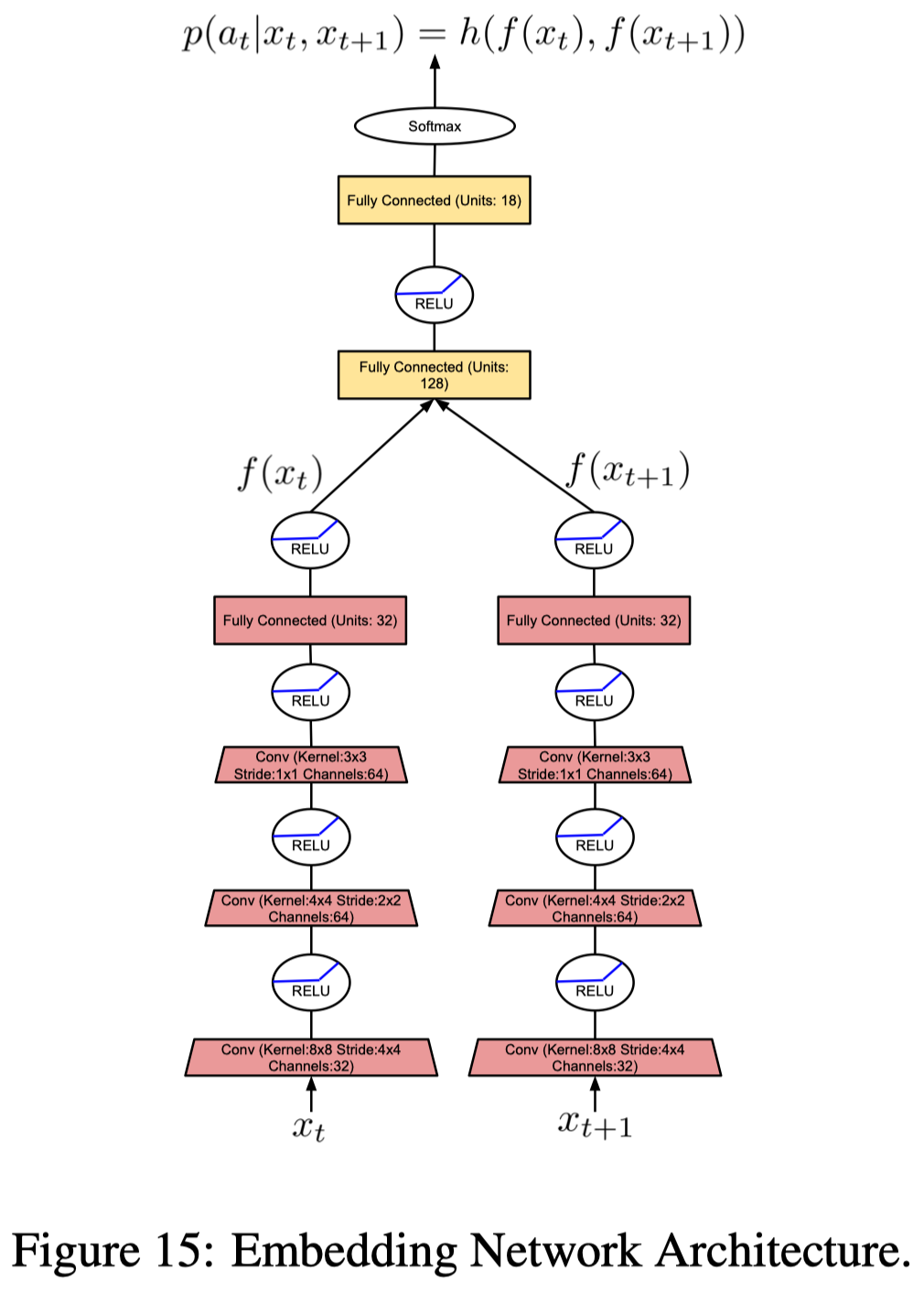

In order to compute the episodic intrinsic reward, the agent maintains an episodic memory \(M\), which keeps track of the controllable states in an episode. A controllable state is a representation of an observation produced by an embedding function \(f\). It’s controllable as the function \(f\) is learned to ignore aspects of an observation that are not influenced by an agent’s actions. In practice, NGU trains \(f\) through an inverse dynamics model, a submodule from ICM that takes in \(x_t\) and \(x_{t+1}\) and predicts \(p(a_t\vert x_t,x_{t+1})\) (see Figure 15). The episodic intrinsic reward is then defined as

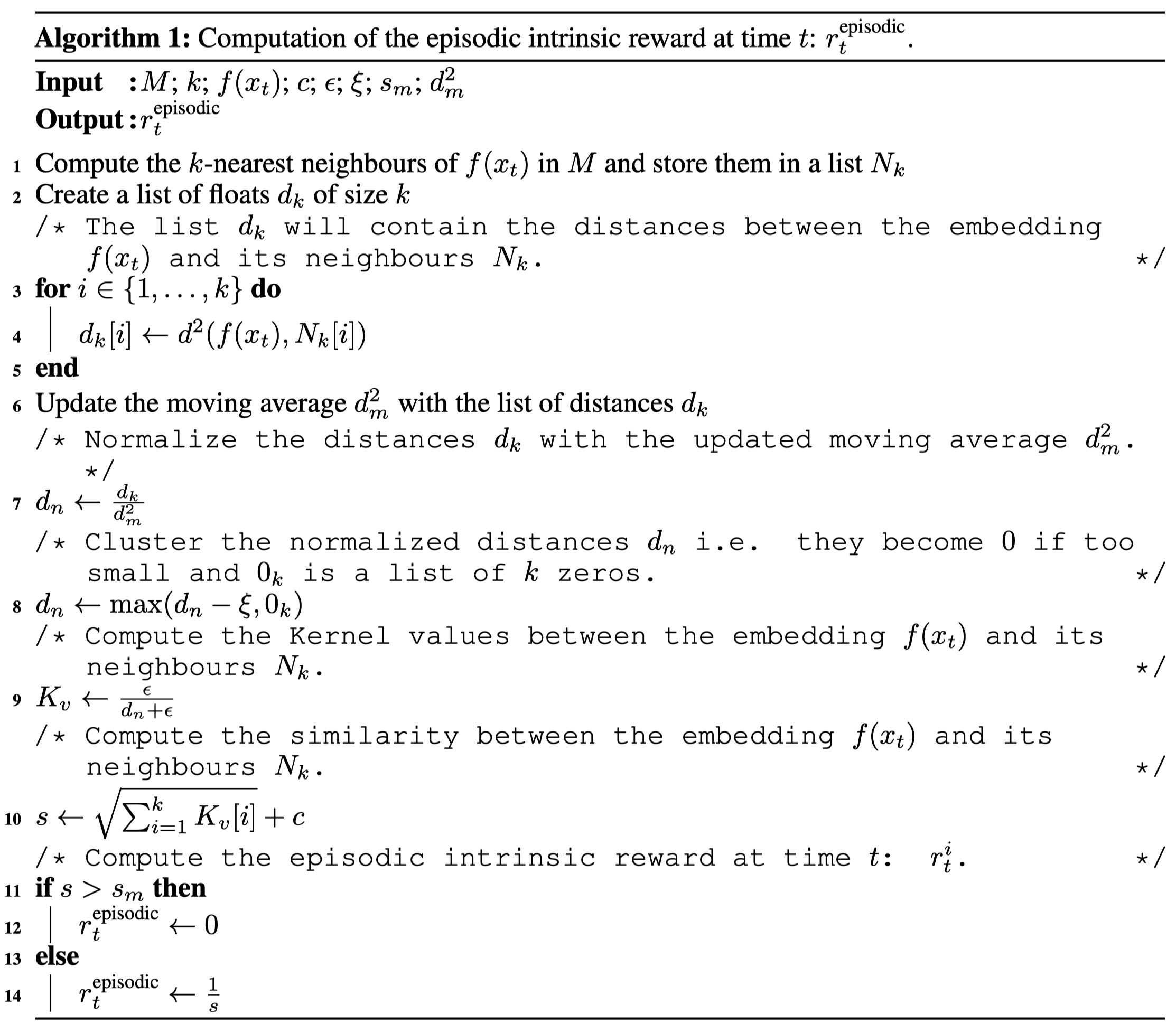

\[\begin{align} r_t^{episodic}={1\over \sqrt{n(f(x_t))}}\approx {1\over\sqrt{\sum_{f_i\in N_k}K(f(x_t),f_i)}+c} \end{align}\]where \(n(f(x_t))\) is the counts for visits to the abstract state \(f(x_t)\), and \(c=10^{-3}\) guarantees a minimum amount of “pseudo-counts”. We approximate these counts \(n(f(x_t))\) as the sum of the similarities given by a kernel function \(K:\mathbb R^p\times \mathbb R^p\rightarrow \mathbb R\), over the content of memory \(M\). In practice, pseudo-counts are computed using the \(k\)-nearest neighbors of \(f(x_t)\) in the memory \(M\), denoted by \(N_k={f_i}_{i=1}^k\). Following [2], we use the inverse kernel for \(K\):

\[\begin{align} K(x,y)={\epsilon\over {d^2(x,y)\over d_m^2}+\epsilon} \end{align}\]where \(\epsilon=10^{-3}\), \(d\) is the Euclidean distance and \(d_m^2\) is the running average of the squared Euclidean distance of the \(k\)-th nearest neighbors. This running average is used to make the kernel more robust to the task being solved, as different tasks may have different typical distances between learned embeddings. Algorithm 1 details the process

Life-Long Novelty Module

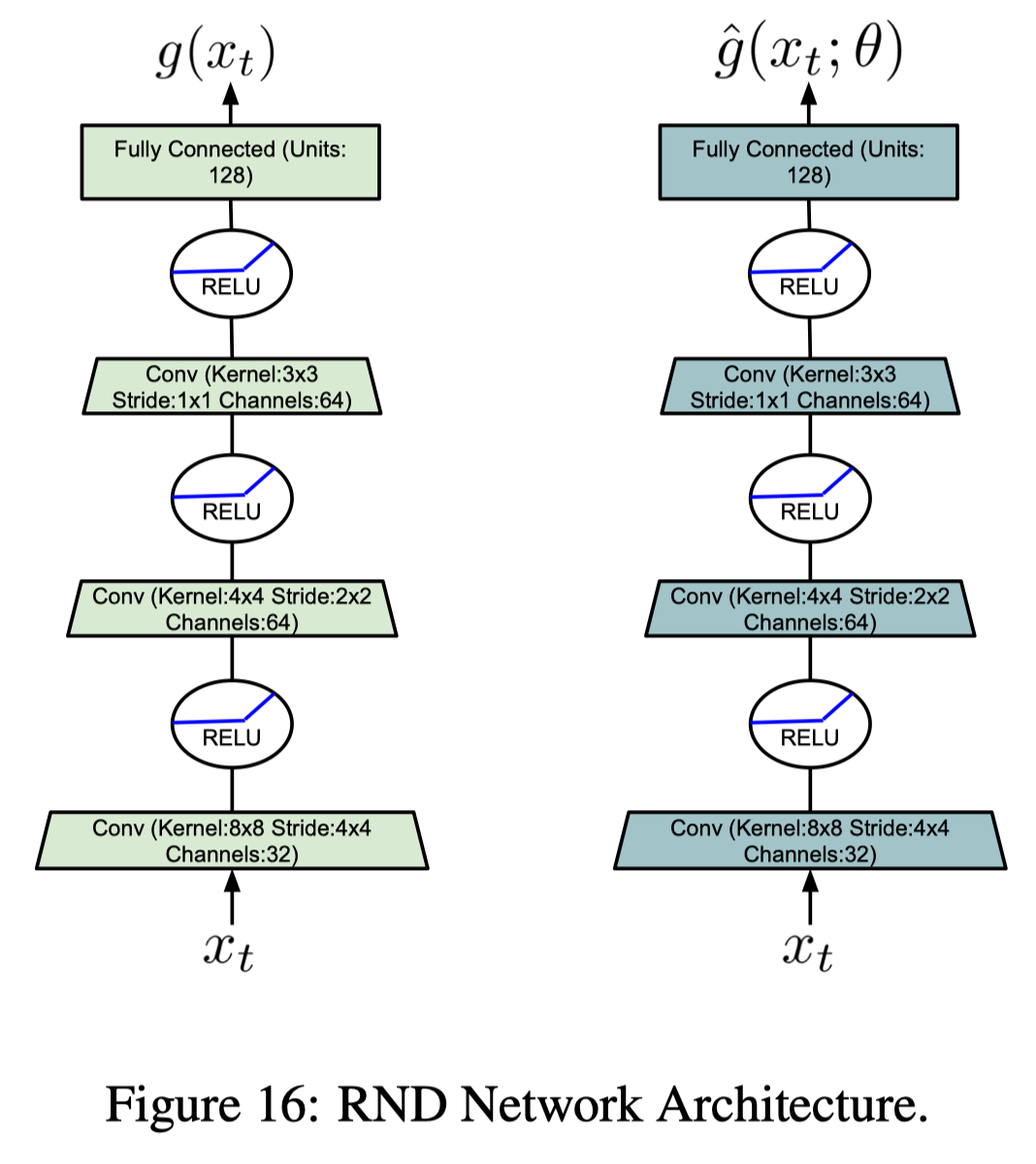

Puigdomènech Badia et al. uses the RND to compute the life-long curiosity, which trains a predictor network \(\hat g\) to approximate a random network \(g\). The life-long novelty is then computed as a normalized mean squared error:

\[\begin{align} \alpha_t=&1+{err(x_t)-\mu_e\over\sigma_e}\\\ \quad err(x)=&\Vert g-\hat g\Vert^2 \end{align}\]where \(\mu_e\) and \(\sigma_e\) are running mean and standard deviation for \(err(x)\). Adding \(1\) here because it now serves as a scale factor. Figure \(16\) shows the architecture of RND

The Never-Give-Up Agent

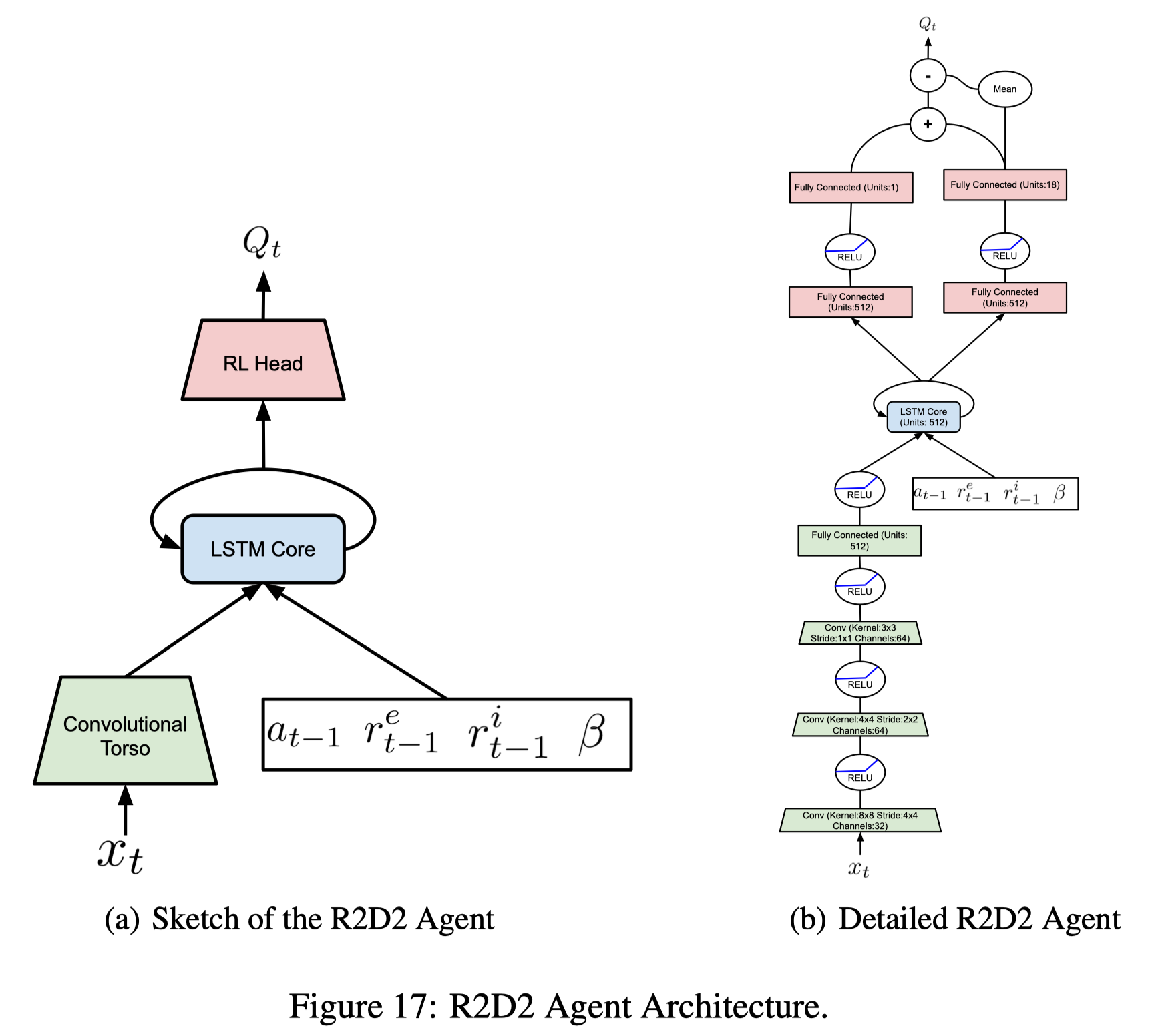

UVFA: The NGU agent uses a Universal Value Function Approximator(UVFA) \(Q(x,a,i)\) to simultaneously approximate the optimal value function with respect to a family of augmented rewards of the form \(r^{\beta_i}t=r^e_t+\beta_i r^i_t\), where the intrinsic reward coefficient \(\beta_i\) is a discrete value from the set \({\beta_i}{i=0}^{N-1}\)(we delay the discussion of the choice of \({\beta_i}_{i=0}^{N-1}\) to the end of this section). The advantage of learning a larger number of policies comes from the fact that exploitative and exploratory policies could be quite different from a behavior standpoint. Having a larger number of policies that change smoothly allows for more efficient training. One may regard jointly training the exploration policies, i.e. \(\beta_i>0\), as training auxiliary tasks, which helps train the shared architecture.

Network architecture: The NGU agent augments the R2D2 agent with the dueling heads and additional inputs (see Figure 17). The additional inputs are included to help alleviate the complex of POMDP as using intrinsic rewards subltly change the underlying MDP, especially if the augmented reward varies in ways unpredicatable from the action and states. Notice that, differing from RND, NGU does not use separate value heads for the intrinsic and extrinsic rewards.(well, later Agent57 uses separate \(Q\)-network for intrinsic and extrinsic rewards)

\[\begin{align} r=r^e+𝛽*r^i,\quad\text{where the discrete coefficient }\beta\in\{\beta_j\}_{j=0}^{N-1} \end{align}\]RL loss: As the agent is trained with sequential data, Puigdomènech Badia et al. use a hybrid of Retrace(\(\lambda\)) and the transformed Bellman operator. This gives us the following transformed Retrace operator

\[\begin{align} \mathcal T^hQ(s_t,a_t):=h\left(h^{-1}(Q(s_t,a_t))+\sum_{k=t}^{t+n-1}\gamma^{k-t}\left(\prod_{i=t+1}^k c_i\right)\Big(r_k+\gamma\mathbb E_{\pi}h^{-1}(Q(s_{k+1},\cdot))-h^{-1}(Q(s_k,a_k))\Big)\right)\tag {1} \end{align}\]Like DQN, this operator is computed using the target network.

Distributed training: The GRU agent follows the same distributed architecture as R2D2, each actor with its own \(\beta_i\). One may boost the performance following SEED to utilize GPU for inference.

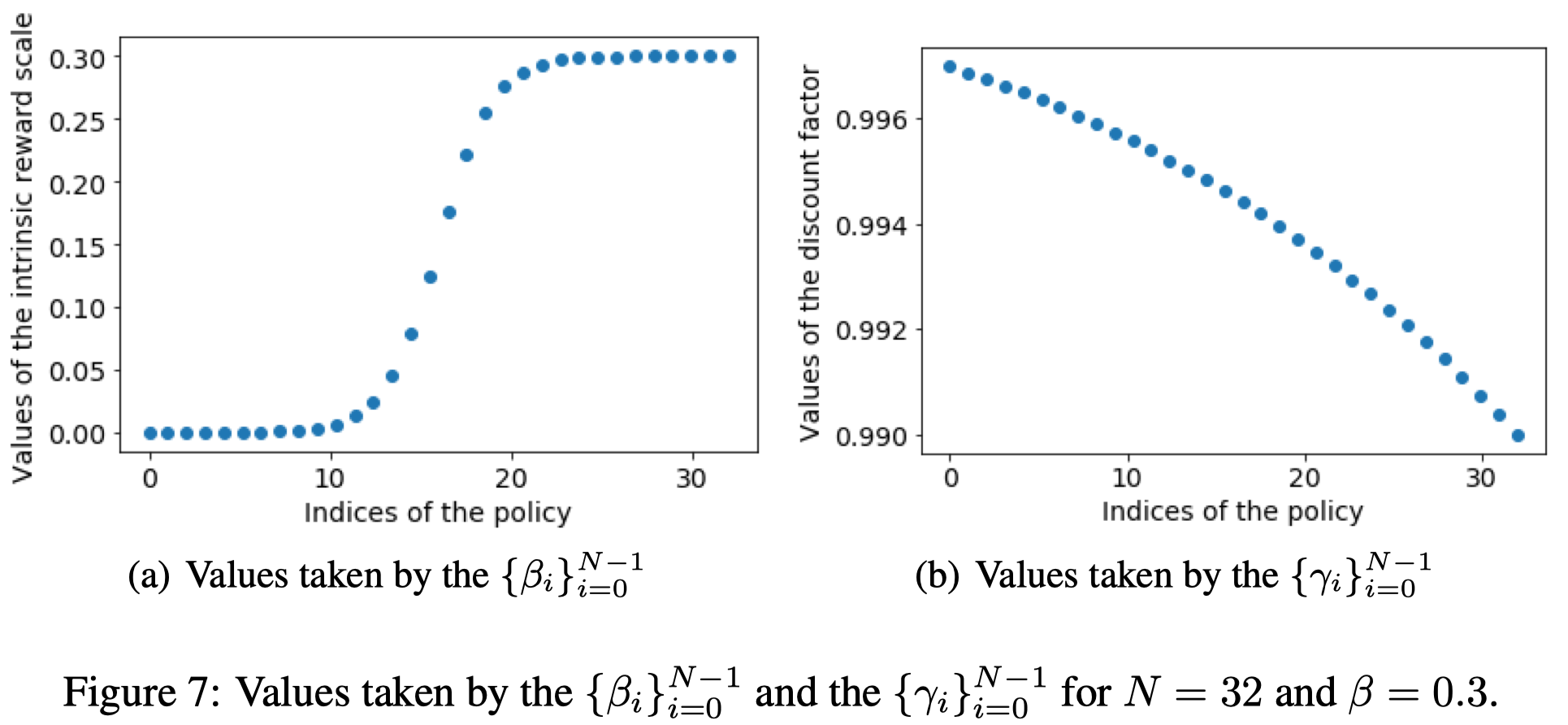

\(\beta\) and \(\gamma\): In the experiments, they use the following \(\beta_i\):

\[\begin{align} \beta_i=\begin{cases} 0&\text{if }i=0\\\ \beta=0.3&\text{if }i=N-1\\\ \beta\sigma(10{2i-(N-2)\over N-2})&otherwise \end{cases} \end{align}\]where \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function, and \(N=32\) is the number of available choices of \(\beta_i\). This choice allows to focus more on the two extreme cases which are the fully exploitative and very exploratory policy. In addition, they associate for each \(\beta_i\) a \(\gamma_i\) such that

\[\begin{align} \gamma_i=1-\exp\left({(N-1-i)\log(1-\gamma_\max)+i\log(1-\gamma_\min)\over N-1}\right)\\\ \gamma_\max=0.997,\gamma_\min=0.99 \end{align}\]This form allows the discounted factors evenly spaced in log-space between \(\gamma_\max\) and \(\gamma_\min\) (see Figure 7). This scheme associates the exploitative policy with the highest discount factor and the most exploratory policy with the smallest discount factor. We use smaller discount factors for exploratory policies because the intrinsic reward is dense and the range of values is small, where we would like the highest possible discount factor for the exploitative policy in order to be as close as possible to optimizing the undiscounted return.

Experimental Results

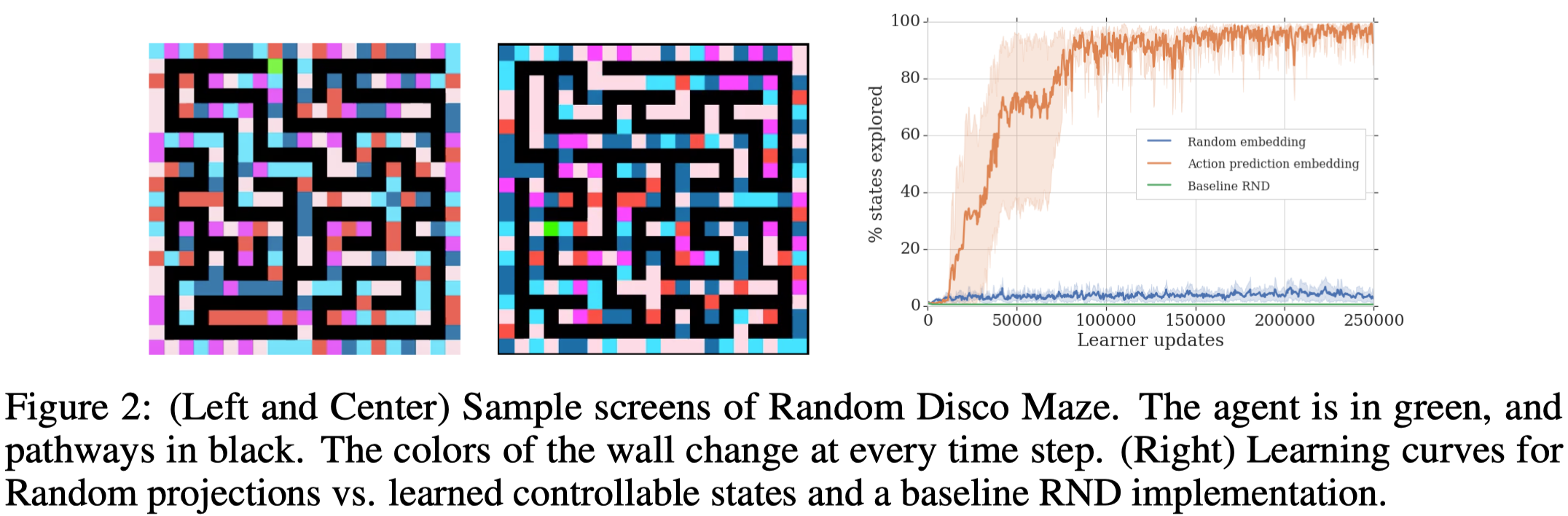

Random Disco Maze

The author run the NGU agent in a gridworld environment, depicted in Figure 2. Each episode begins with the agent in a randomly generated maze and ends when the agent step into a wall. At every time step, the color of each wall fragment is randomly sampled from a set of five possible colors, making the state space enormous and unpredictable. To test the agent’s exploratory ability, no external reward is given. As Figure 2(Right) shows, the GRU agent can effectively explore the state while the other two fail, showing that the embedding function \(f\) can effectively distill controllable aspects of the environment. More interestingly, the NGU agent is able to learn a strategy that resembles deep-first search.

Atari

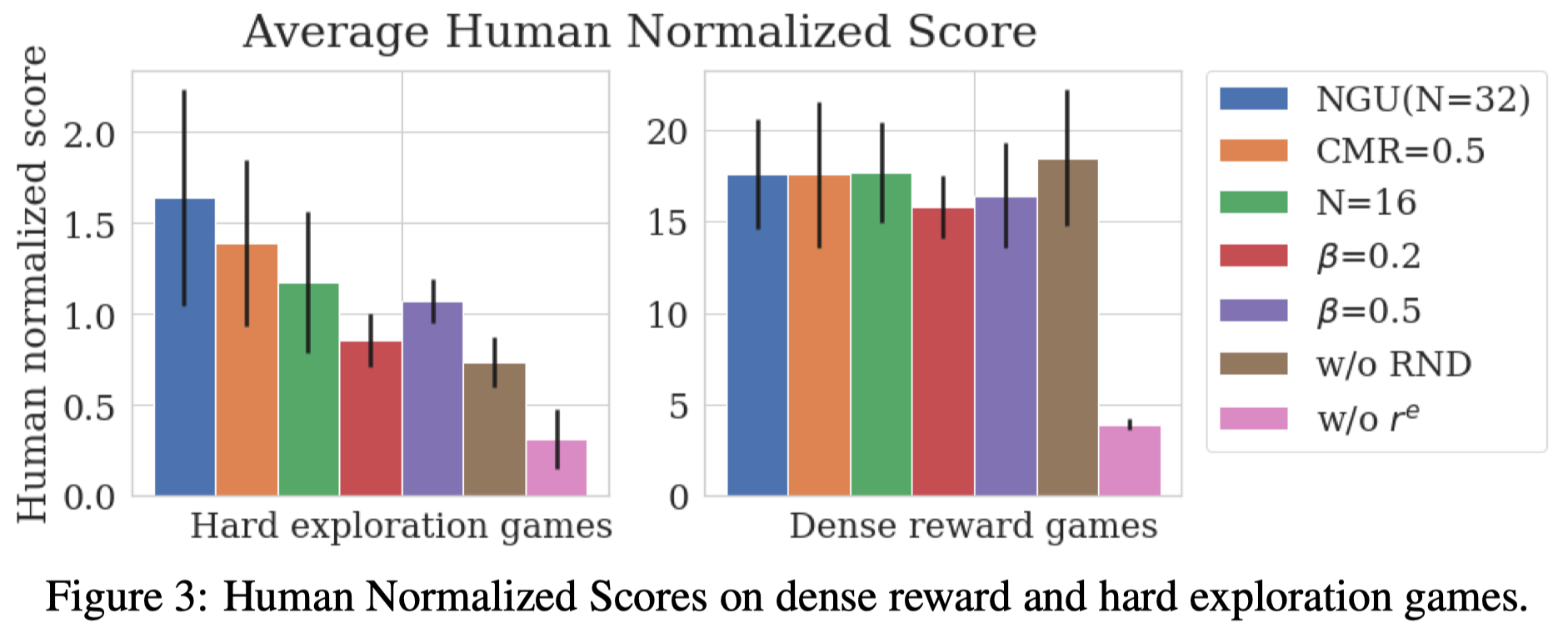

We briefly summarize a few experimental results on Atari as follows

- There is no single best hyperparameters for all environments; different trade-offs, which are often not obvious, have to be made for each environment. Even though, we can still draw some conclusions in general sense.

- Sharing experience from all the actors slightly harms overall average performance on hard exploration games; it is better to train each policy with data produced by the same \(\beta_i\). This suggests that the power of acting differently for different conditioning mixtures is mostly acquired through the shared weights of the model rather than shared data. However, Montezuma’s Revenge provides an exception, which performs better when training with equal amounts of data produced by \(\beta_i\) and \(\beta_{j\ne i}\).

- A large number of mixtures \(N\) improves the performance on hard exploration games. However, a large \(N\) sometimes impairs the performance on dense reward games, such as Breakout.

- The maximum intrinsic coefficient \(\beta=0.3\) results in the best averaging performance, where \(\beta=0.2\) and \(\beta=0.5\) make the performance worse on hard exploration games. This suggest a delicate balance between intrinsic and extrinsic reward is often required.

- The RND is greately beneficial on hard exploration games. This matches the argument that long-term intrinsic rewards have a great impact.

- NGU is robust to its hyperparameters on the dense reward games: as extrinsic rewards become dense, intrinsic rewards natually become less relevant

- Even without extrinsic reward \(r^e\), we can still obtain average superhuman performance on the evaluated dense reward games, indicating that the exploration policy of NGU is an adequate high performing prior for this set of games. This confirms the findings of Burda et al. 2018, where they showed that there is a high degree of alignment between the intrinsic curiosity objective and the hand-designed extrinsic rewards of many game environments.

- The heuristics of surviving and exploring what is controllable seem to be highly general and beneficial.

What’s left?

As Badia&Piot&Kapturowski et al. 2020 point out in Agent57, the NGU agent suffers from two drawbacks:

- NGU collects the same amount of experience following each of its policies, regardless of their contribution to the learning process.

- In practice, NGU can be unstable and fail to learn an appropriate approximation of \(Q_{r^i}^*\) for all the state-action value functions in the family, even in simple environments. This is especially the case when the scale and sparseness of \(r^e\) and \(r^i\) are both different, or when one reward is more noisy than the other. They conjecture that learning a common state-action value function for a mix of rewards is difficult when the rewards are very different in nature.

We leave detailed discussion about Agent57 to the next post.

References

-

Badia, Adrià Puigdomènech, Pablo Sprechmann, Alex Vitvitskyi, Daniel Guo, Bilal Piot, Steven Kapturowski, Olivier Tieleman, et al. 2020. “Never Give Up: Learning Directed Exploration Strategies,” 1–28. http://arxiv.org/abs/2002.06038.

-

Charles Blundell, Benigno Uria, Alexander Pritzel, Yazhe Li, Avraham Ruderman, Joel Z Leibo, Jack Rae, Daan Wierstra, and Demis Hassabis. Model-free episodic control. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.04460, 2016.

-

Alexander Pritzel, Benigno Uria, Sriram Srinivasan, Adrià Puigdomènech, Oriol Vinyals, Demis Hassabis, Daan Wierstra, and Charles Blundell. Neural episodic control. ICML, 2017.

-

Yuri Burda, Harri Edwards, Deepak Pathak, Amos Storkey, Trevor Darrell, and Alexei A Efros.

Large-scale study of curiosity-driven learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.04355, 2018a.

-

Badia, Adrià Puigdomènech, Bilal Piot, Steven Kapturowski, Pablo Sprechmann, Alex Vitvitskyi, Daniel Guo, and Charles Blundell. 2020. “Agent57: Outperforming the Atari Human Benchmark.” http://arxiv.org/abs/2003.13350.