Introduction

AlphaStar, proposed by Vinyals et al. 2019, is the first AI agent that was rated at the Grandmaster level in the full game of StarCraft II, a real-time strategy game in which players balance high-level economic decisions with individual control of hundreds of units. In this post, we try to present an overview of AlphaStar and distill some essential techniques in the hope that these techniques could be reused in other reinforcement learning projects.

I’d like to especially highlight the thesis by Choi 2020, which reveals a great level of details missed in the original paper.

TL; DR

- Architecture. Two notes from the architecture. 1) Entities are first processed by a transformer to produce embeddings, then by a 1D convolution to further summarize nearby entity embeddings. 2) PtrNets are used when determining selected entity and target units.

- AlphaStar is trained in two phases. First, it’s trained by supervised learning with provided expert data. Then, it’s trained by a policy-gradient algorithm to maximize the win rate against an agent pool.

- In the supervised learning stage, AlphaStar is trained with data from the top players, optionally conditioned on a strategy statistic \(z\) that encodes player’s building order and cumulative statistics.

- In the reinforcement learning stage, the policy maximizes the V-Trace and UPGO and the entropy while the value function minimizes TD(\(\lambda\)). Furthermore, to ensure meaningful exploration, the network is optionally conditioned on the statistic \(z\) and a KL penalty is adopted to encourage the agent to behave similarly to the supervised policy. Finally, L2 regularization is used to prevent overfitting.

- Challenges&Solutions.

- To avoid chasing circles, AlphaStar trains three types of agents in a league: 1) the main agents are trained against all league members including themselves; 2) the main exploiters play against the main agents to find their weaknesses; 3) the league exploiters are trained against all agents in the league to find the global blind spot of the league(strategies no player in the league can defeat but are not necessary to be robust to themselves). PFSP is used to prioritize challenging opponents.

Architecture

Overview

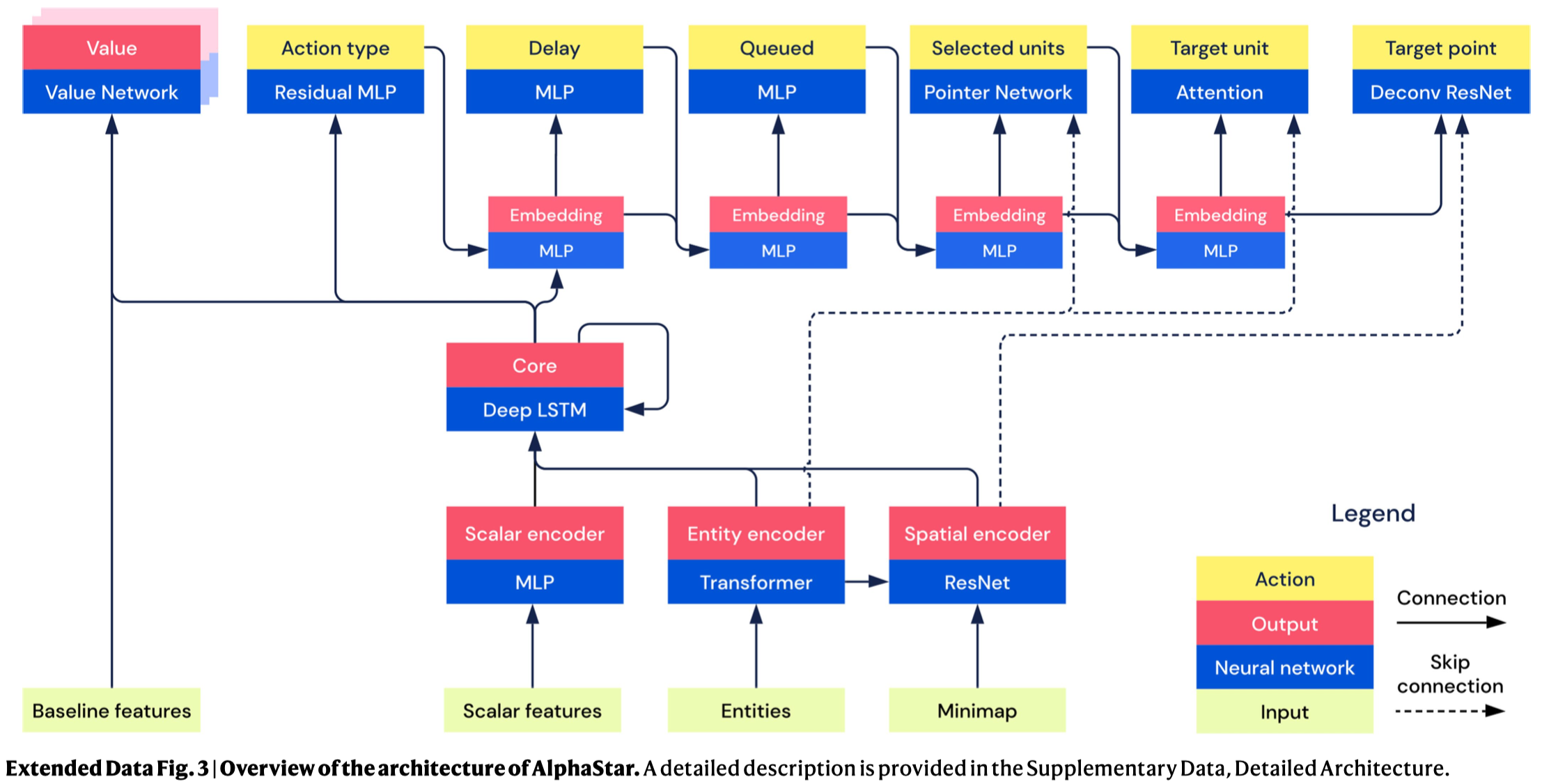

AlphaStar’s policy embeds three types (entity, scalar, and map) of information, concatenates them together, passes that concatenation and previous LSTM states through a deep LSTM, and uses the LSTM output to autoregressively sample each action argument one at a time. The value network uses the LSTM output and additional baseline features to generate a baseline for each reward and pseudo-reward.

Due to the scale of the problem and variability present in reinforcement learning, architecture components were chosen and tuned with respect to their performance in supervised learning. The decision is made based on the accuracies, losses, and performance against AlphaStar players, in which the performance in actual play is the most important metric because, for example, giving the network access to the entire previous action improves accuracies (because humans tend to repeat the same action multiple times) but can lead to worse play (because repeating action is often not a useful strategy)

Policy Network

Data Representation

The entity list is a list of every discrete visible entity, including units, buildings, resources, and intractable terrain, in the game. The list has a maximum size of \(512\), and any entities after \(512\) are ignored. Each entity has a 1D vector of information corresponding to that entity and data in those vectors is preprocessed to either fall within a uniform range around \([0, 1]\) or encoded as a one-hot vector. The preprocessed entities are then fed through a 3-layer transformer with 2-headed self-attention to produce entity embeddings. The mean of entity embeddings is processed through a linear layer(with ReLU) to yield an embedding of all the entities that will be concatenated with data from the map and scalars. Each individual entity embedding is processed through a ReLU, 1D convolution with \(32\) filters, and another ReLU to yield embeddings of each entity that will be used both to enrich the embedding of the map and as a skip connection to help select entity action arguments.

The spatial encoder(a ResNet) embeds the 2D visual information from the map enriched through scatter connections by entity embeddings. The map consists of several layers preprocessed to either fall within a uniform range or to be one-hot.

All data that is not an entity or spatial is embedded by the scalar encoder. This includes the list of available actions, the amount of resources available to players, and the statistics \(z\). Each scalar feature is preprocessed to fall within a uniform range or to be one-hot, and individually embedded by linear layers or small transformers, then concatenated together as the overall scalar embedding. Certain features that are relevant for action type selection (e.g., the statistic \(z\) and available actions) are also concatenated into a separate vector that will be used for action type selection.

The concatenated entity, spatial and scalar embeddings are combined into a single 1D tensor and passed through a 3-layer LSTM.

Action Selection

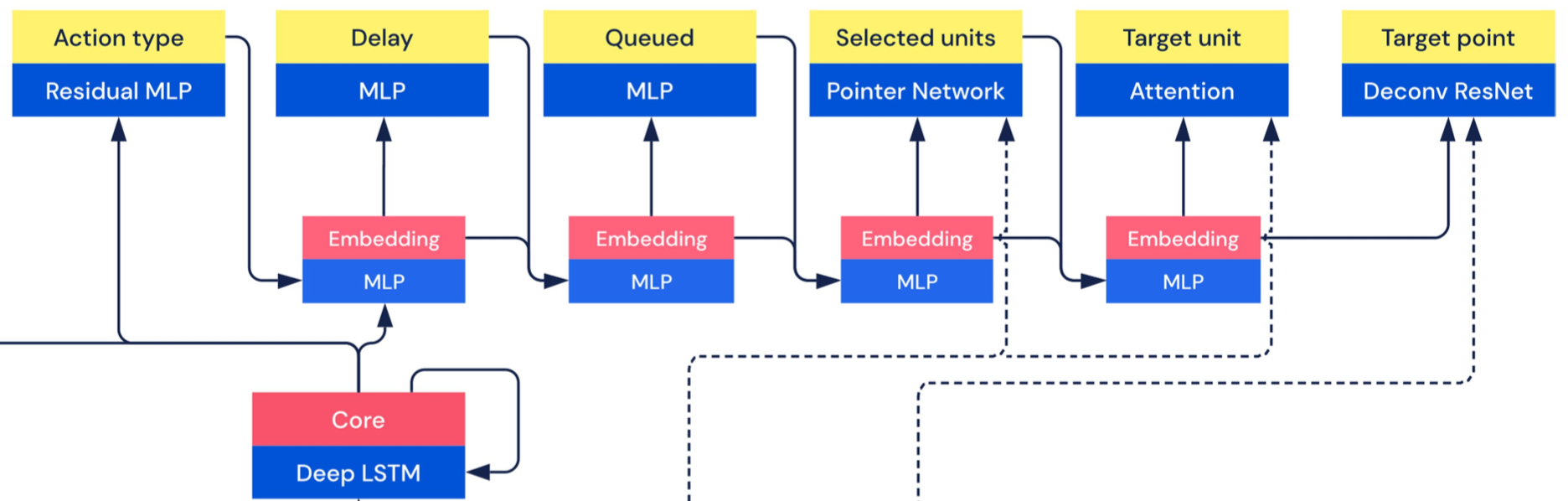

Actions are decomposed into a series of arguments and the network selects each argument autoregressively with the respective head. We briefly introduce these heads below

- The action-type head processes the LSTM output through several residual MLPs and a gated linear unit gated by the scalar information to select the action type.

- The delay head processes the autoregressive embedding through an MLP to select the delay.

- The queue processes the autoregressive embedding through an MLP to determine whether or not to queue the action.

- The selected units head computes a key for each entity corresponding to the entity embedding skip connection, masked by whether or not the entity is a valid selection, and uses those keys in a recurrent pointer network to decide which of up to \(64\) selected entities to apply the action to.

- The target unit head is similar to the selected units head, except selecting a single unit.

- The target point head reshapes the autoregressive embedding to the same shape as the final map skip connections, concatenates the embedding and the skip connections, and processes the concatenation through a series of up-scaling convolutions, Gated ResBlocks (gated by the autoregressive embedding), and FiLM layers to select the location arguments.

It’s interesting that the target point head uses FiLM layers, a general-purpose conditioning method originally developed for visual reasoning, but what is it conditioned on?

Value Network

There are multiple value networks for each type of reward and pseudo-rewards. Besides the information available for the policy network, value networks also have access to privileged information that is not available to the policy network, like the opponent observations.

AlphaStar Overview

We first present the overall training process of AlphaStar, a more detailed discussion on some advanced techniques is delayed to the next section.

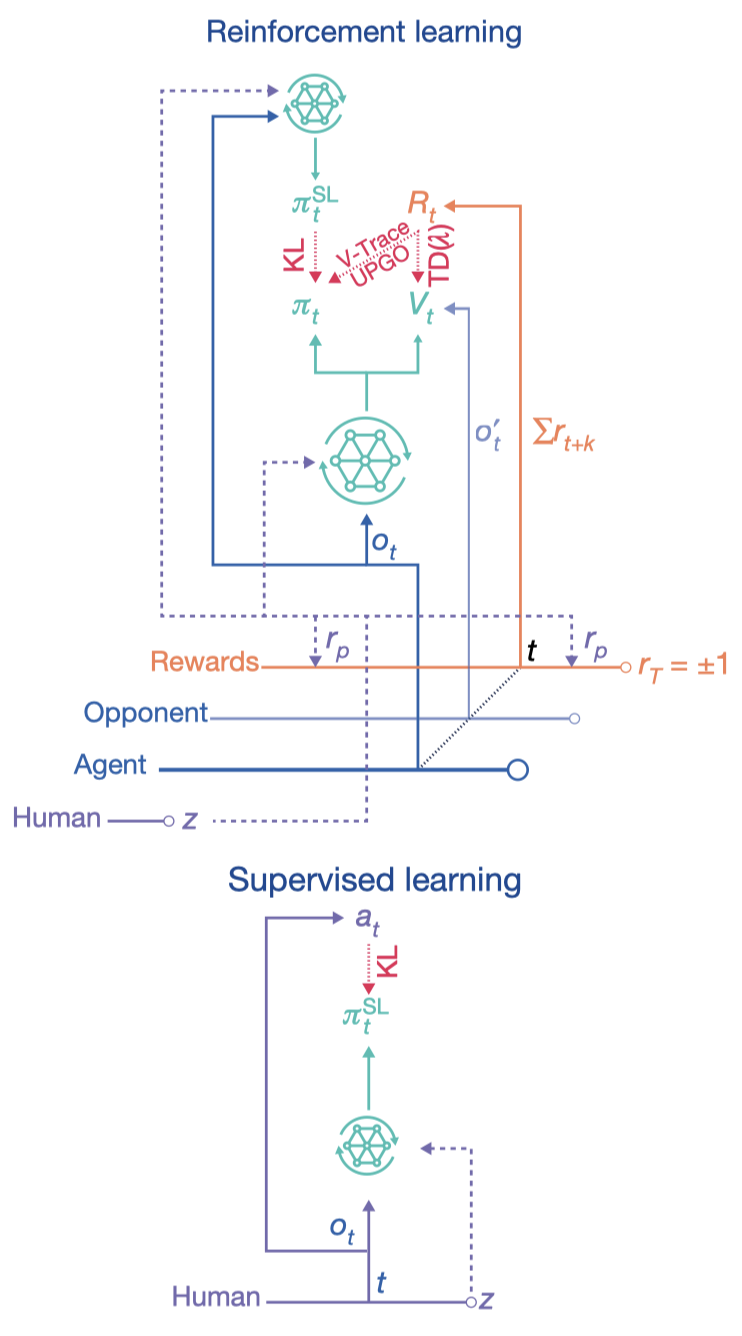

The training process of AlphaStar is divided into two phases: AlphaStar is first trained by supervised(imitation) learning with provided human data. After that, it’s trained by a policy-gradient reinforcement learning algorithm that’s designed to maximize the win rate against a mixture of opponents.

Supervised Learning

In the supervised learning stage, AlphaStar is trained with replays from the top \(22\%\) of players with MMR scores(match making rating, a Blizzard’s metric similar to Elo) greater than 3,500. The policy is optionally conditioned on a strategy statistic \(z\) in both supervised and reinforcement learning; in supervised learning, we set \(z\) to zero \(10\%\) of the time. The policy is trained by computing the KL divergence between human and agent actions. Adam optimizer is selected for update and \(L_2\) regularization is applied to ameliorate overfitting.

The policy was further fine-tuned using only winning replays with MMR above 6,200. Fine-tuning improved the win rate against the built-in elite bot from \(87\%\) to \(96\%\) in Protoss versus Protoss games.

Reinforcement Learning

The reinforcement learning algorithm adopted by AlphaStar is based on an asynchronous policy-gradient algorithm, namely IMPALA. Because the current and previous policies are highly unlikely to match over many steps in large action spaces, some policy correction mechanism must be employed to compensate the distribution mismatch and whereby enabling off-policy learning. Consequently, three objectives are employed by AlphaStar: the policy is updated with V-trace and upgoing policy update(UPGO), and the value function are updated using TD(\(\lambda\)). We briefly address each objective in the following sub-sections.

V-Trace

V-trace is employed for the policy update to correct the policy mismatch:

\[\begin{align} \max_\pi\mathbb E_{(s_t,a_t,s_{t+1})\sim\mu}&[\rho_t(r_t+\gamma v(s_{t+1}, z)-V(s_t, z))\log\pi(a_t|s_t, z)]\\\ \text{where}\quad v(s_t, z) &= V(s_t,z )+\sum_{k=t}^{t+n-1}\gamma^{k-t}\left(\prod_{i=t}^{k-1}c_i\right)\delta_kV\\\ \delta_kV&=\rho_k(r_k+\gamma V(s_{k+1}, z)-V(s_k, z))\\\ c_{i}&=\lambda \min\left({\pi(a_i|s_i,z)\over \mu(a_i|s_i,z)}, \bar c\right)\\\ \rho_k&=\min\left({\pi(a_k|s_k,z)\over \mu(a_k|s_k,z)}, \bar\rho\right) \end{align}\]where \(V\) is the value function, truncated levels \(\bar c\) and \(\bar\rho\) are hyperparameters(usually set to 1), \(\pi\) and \(\mu\) are the current and behavior policy, respectively, \(\lambda\) is a discount factor that controls the bias-variance trade-off by exponentially discounting the future error.

When applying V-trace to the policy in large action spaces, the off-policy correction truncates the trace early; to mitigate this problem, we assume independence between the action type, delay, and all other arguments, and so update the components of the policy separately.

UPGO

The upgoing policy update objective(UPGO), built on the idea of self-imitation learning, is defined as

\[\begin{align} \max_\pi&\rho_t(G_t^U-V(s_t,z))\log\pi(a_t|s_t,z)\\\ \text{where}\quad G_t^U=&\begin{cases}r_t+G_{t+1}^U&\text{if }Q(s_{t+1},a_{t+1},z)\ge V(s_{t+1},z)\\\ r_t+V(s_{t+1},z)&\text{otherwise}\end{cases}\\\ \rho_t=&\min\left({\pi(a_t|s_t,z)\over\mu(a_t|s_t,z)},1\right)\\\ Q(s_t,a_t,z)=&r_t+V(s_{t+1},z) \end{align}\]The idea is to update the policy from partial trajectories with better-than-expected returns—the “if” part—and by bootstrapping when the behavior policy takes a worse-than-average action—the “otherwise” part. Notice that action-values are approximated by the one-step target since it’s hard to approximate it over the large action space of StarCraft.

Unlike V-trace and TD(\(\lambda\)), which is applied for each reward, UPGO is only used for the win-loss reward.

TD(\(\lambda\))

TD(\(\lambda\)) uses the exponentially-weighted average of all \(n\)-step returns as the target:

\[\begin{align} G_t^{\lambda}&=(1-\lambda)\sum_{n=1}^\infty\lambda^{n-1}G_t^{(n)}\\\ &=r_t+(1-\lambda)\gamma V(s_{t+1})+\lambda \gamma G_{t+1}^\lambda\\\ \text{where}\quad G_t^{(n)}&=\sum_{i=0}^{n-1}\gamma^ir_{t+i}+\gamma^n V(s_{t+n}, z) \end{align}\]Though biased, this choice is preferred over the V-trace because Vinyals et al. 2019 found existing off-correction methods (including V-trace) can be inefficient in large, structured action space as distinct actions can result in similar (or even identical) behavior but exhibit significantly different importance ratios, which in turn results in estimates of high variance.

As we will see later, there are multiple pseudo-rewards, and AlphaStar trains a value function for each of them. Furthermore, value functions are trained with additional opponent’s observations as input to reduce variance—this makes sense since value update is mainly built on the Bellman equation, which is based on the assumption of Markov property. Furthermore, this also helps to ameliorate the non-stationarity presented in multi-agent environments, effectively improving the agent’s final performance.

Overall loss

The final loss is a weighted sum of the above objectives, corresponding to the win-loss reward \(r_t\) as well as pseudo-rewards based on human data, the KL divergence loss with respect to the supervised policy, and the standard entropy regularization loss.

Advanced Techniques

Challenges

We first identify a few challenges presented by StarCraft:

- Partial observability: Observation is imperfect; as it’s with human players, opponent units outside the camera view cannot be observed. This requires agents to learn how to effectively explore the map and infer the opponent’s strategy from incomplete data.

- High-dimensional action space: The action space is huge and highly structured; each action needs to specify what action type to issue, whom it is applied to, where it targets, and when the next action will be issued. This results in approximate \(10^{26}\) possible choices at each step.

- Delay: Humans play StarCraft under physical constraints that limit their reaction time and the rate of their actions. Similar constraints are imposed upon AlphaStar. Observations and actions are delayed due to network latency and computation time.

- Long planning horizon. Each game may extend more than ten minutes. This includes tens of thousands of time steps and thousands of actions, which potentially makes the credit-assignment problem hard to deal with.

- Hard exploration: Due to domain complexity and reward sparsity, exploration is difficult. Furthermore, discovering novel strategies is intractable with naive self-play exploration methods; and those strategies may not be effective when deployed in real-world play with humans.

- Game theory: StarCraft features a vast space of cyclic, non-transitive strategies and counter-strategies. As such, there is no single best strategy and an agent has to continually explore and expand the frontiers of strategic knowledge.

We concisely summarize each solution as follows—notice that these are not one-to-one maps; there are definitely more complex relations involved. I just pick up what I think contributes most to each challenge.

- The partial observability is addressed by the deep LSTM system.

- The structured, combinatorial action space is managed by a pointer network and an auto-regressive policy, where the pointer network selects the target object and the auto-regressive policy allows to choose one action based on some of the others.

- Delay is addressed by a delay head, which outputs the logits corresponding to each delay.

- The long planning horizon is handled by the combination of supervised learning and reinforcement learning. Maybe supervised learning contributes most to it as we can see from the following video.

- Hard exploration is solved by human data.

- Game-theoretic challenges are addressed by league training, a multi-agent reinforcement learning framework designed both to address the cycles commonly encountered during self-play training and to integrate a diverse range of strategies.

We will focus on 5 and 6 in the remaining of this section.

Hard Exploration

Devising novel strategies requires deep exploration with a series of precise instructions over thousands of steps. It is highly improbable for naive exploration to achieve that. Consequently, Vinyals et al. 2019 utilize human data to encourage robust behavior against likely human play:

-

All policy parameters are initialized to the supervised policy and continually minimize the KL divergence between the supervised and current policy.

-

During reinforcement learning, we condition the main agents on the strategy statistic \(z\), randomly sampled from human data. The agents receive pseudo-rewards for following the strategy corresponding to \(z\). Each type of pseudo-reward is active (that is, non-zero) with probability \(25\%\), and separate value functions and losses are computed for each pseudo-reward. This human exploration ensures that a wide variety of relevant modes of play continue to be explored throughout training.

Game-theoretic Challenges

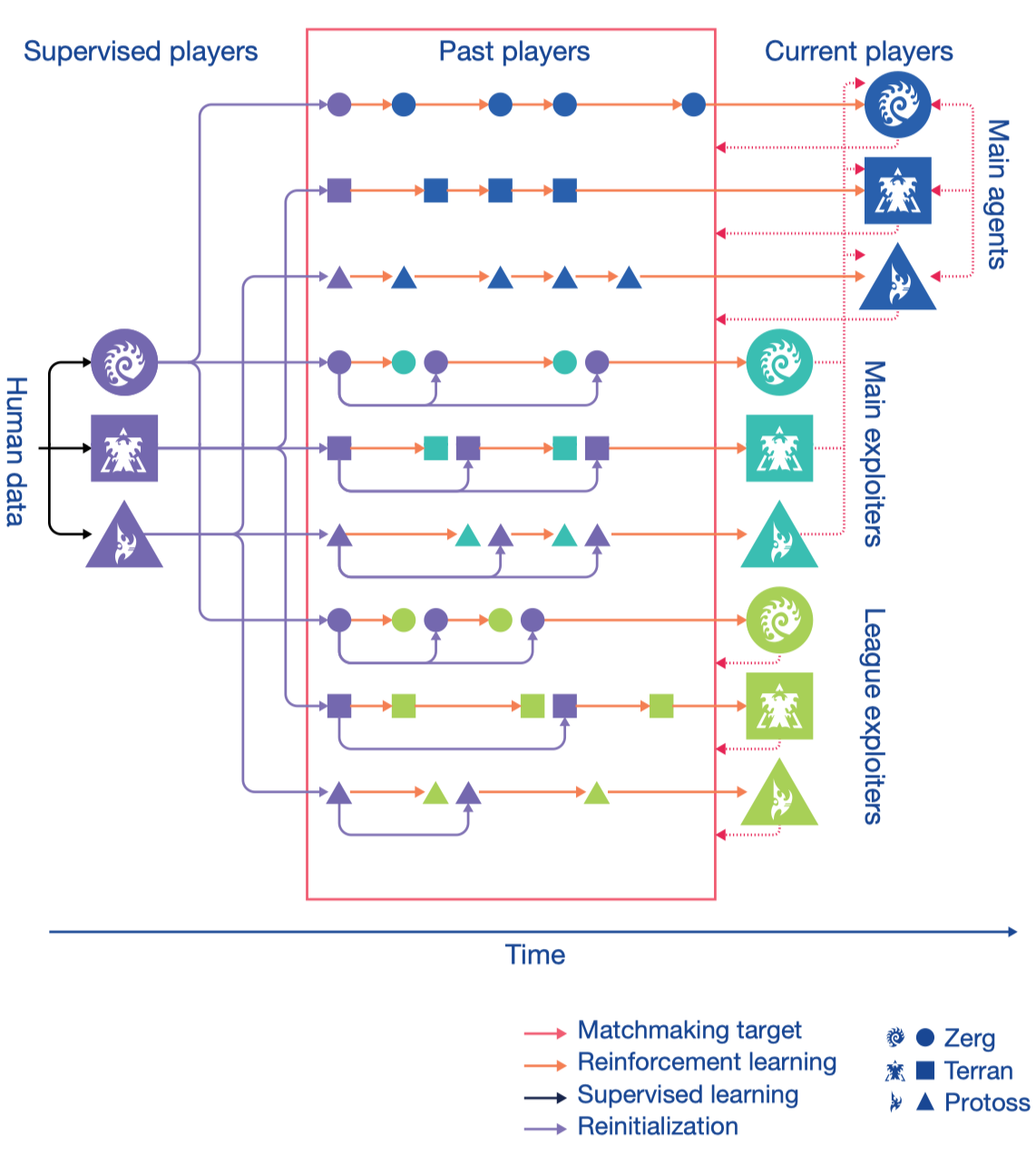

As there is a vast space of cyclic, non-transitive strategies and counter-strategies in StarCraft, self-play algorithms may easily chase circles(for example, where A defeats B, and B defeats C, but A loses to C) indefinitely without making progress because of forgetting. Therefore, the authors propose to use league training to tackle cycles and to master a diverse range of strategies.

From Self-play to Prioritized Fictitious Self-play

League training maintains a league of players, populated by regularly saving copies of agents as new players during RL training. Then the latest agents play with all previous players in the league. This mechanism, known as fictitious self-play(FSP), helps handle cycles in the self-play approach. However, uniformly sampling opponents can be wasteful as it is pointless to play with opponents that the agent has always defeated. Consequently, the authors introduce prioritized fictitious self-play(PFSP) that samples an agent’s opponent based on the probability that the agent can beat the opponent. Mathematically, for an agent \(A\), we sample the opponent \(B\) from a candidate set \(\mathcal C\) with probability

\[\begin{align} f(P(A\text{ beats }B))\over\sum_{C\in\mathcal C}f(P(A\text{ beats }C)) \end{align}\]where \(f:[0,1]\rightarrow [0,\infty]\) is some weighting function.

Vinyals et al. 2019 choose \(f_{\text{hard}}=(1-x)^p\) to make PFSP focus on the hardest players, where \(p\in R_+\) controls how entropic the resulting distribution is. By focusing on the hardest players, the agent must beat everyone in the league rather than maximizing average performance—the latter is alluded by FSP. This scheme helps with integrating information from exploits, as these are strong but rare counter strategies, and a uniform mixture would be able to just ignore them.

Only playing against the hardest opponents can be inefficient since the agent may never win and fail to learn anything. Therefore, PFSP also uses an alternative curriculum, \(f_{var}(x)=x(1-x)\), where the agent preferentially plays against opponents around its own level. This curriculum is used for main exploiter and struggling main agents to facilitate learning.

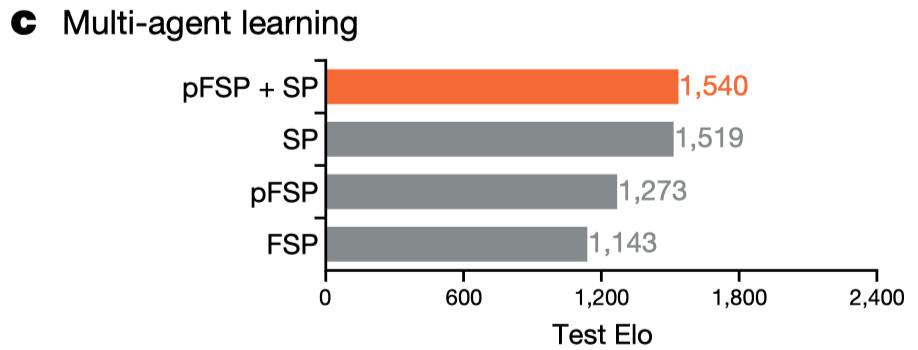

Types of Agents in League

The league consists of three types of agents: three main agents(one for each race), three main exploiters(one for each race), and six league exploiters(two for each race). They differ primarily in their mechanism for selecting the opponent mixture, when they are saved to create a new player, and the probability of resetting to the supervised parameters:

- Main agents are trained with \(35\%\) SP, \(50\%\) PFSP against all past players in the league, and an additional \(15\%\) of PFSP matches against strong main players or main exploiters the agent can no longer beat. If there are no such strong players, the \(15\%\) is used for self-play instead. As we’ve discussed, PFSP provides the agent with more opportunities to overcome the most problematic opponents, and SP speeds up the learning process. Every \(2\times 10^9\) steps, a copy of the agent is added as a new player to the league. Main agents never reset.

- Main exploiters play against the current iteration of main agents. Their purpose is to identify the potential weaknesses of the main agents and consequently make them more robust. Half of the time, and if the current winning rate is lower than \(20\%\), main exploiters use PFSP with \(f_{var}\) weighting over players created by the main agents. These agents are added to the league whenever all three main agents are defeated in more than \(70\%\) of games, or after a timeout of \(4\times 10^9\) steps. They are then reset to the supervised parameters.

- League exploiters are trained using PFSP and their frozen copies are added to the league when they defeat all players in the league in more than \(70\%\) of games, or after a timeout of \(2\times10^9\) steps. At this point, there is a \(25\%\) probability that the agent is reset to the supervised parameters. The main point of league exploiters is to identify global blind spots in the league (strategies that no player in the league can beat, but that are not necessarily robust themselves).

Both main exploiters and league exploiters are periodically reinitialized to encourage more diversity and may rapidly discover specialist strategies that are not necessarily robust against exploitation.

References

- Vinyals, Oriol, Igor Babuschkin, Wojciech M. Czarnecki, Michaël Mathieu, Andrew Dudzik, Junyoung Chung, David H. Choi, et al. 2019. “Grandmaster Level in StarCraft II Using Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning.” Nature 575 (November). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1724-z.

- Choi, David. 2020. “AlphaStar : Considerations and Human-like Constraints for Deep Learning Game Interfaces By.”

- Luke Metz, Julian Ibarz, Navdeep Jaitly, and James Davidson. Discrete sequential prediction of continuous actions for deep RL. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.05035, 2017.

- DeepMind Blog: https://deepmind.com/blog/article/alphastar-mastering-real-time-strategy-game-starcraft-ii

- Nature Page: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1724-z

Supplementary Materials

Observation

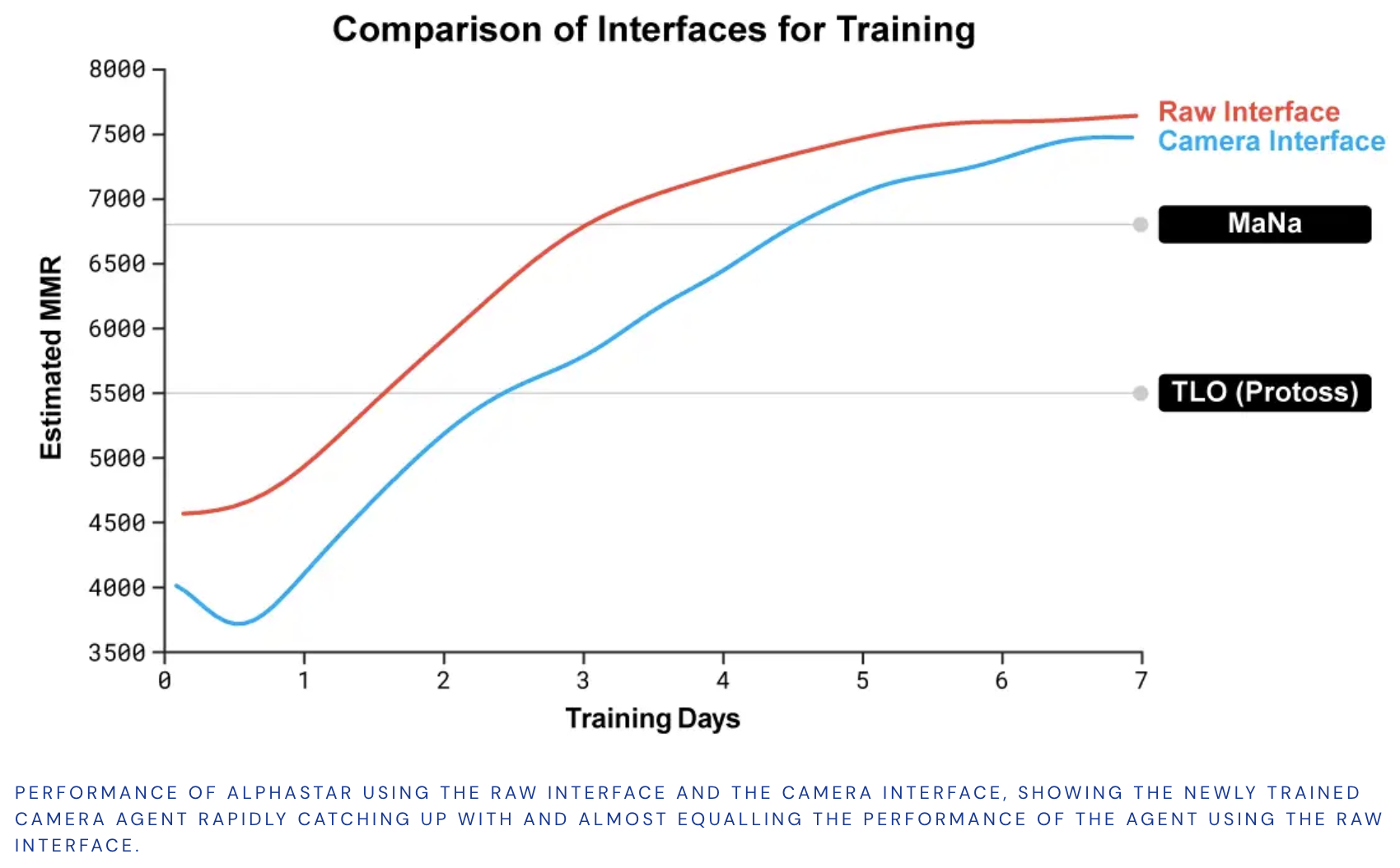

There are two versions of AlphaStar. The first version directly observes the attributes of its own and its opponent’s visible units on the map, without having to move the camera. The second version can choose when or where to move the camera. Its perception is restricted to on-screen information, and action locations are restricted to its viewable region. The following figure demonstrate the performance of these two different versions. We can see that though the second version struggles in the beginning, it works pretty well at the end and reaches comparable performance to the first version.

Rewards

There are two types of rewards.

- The win-loss reward is not discounted so that the agent takes a longer term strategic view and does not converge to “rush” strategies that can be executed quickly.

- The pseudo-rewards measure the edit distance between sampled and executed build orders, and the Hamming distance between sampled and executed cumulative statistics

Scatter Connection

A scatter connection refers to the process that scatters entity embeddings into the map layer so that the entity at a specific location corresponds to the unit placed there.

Strategy Statistic \(z\)

The statistic \(z\) is extract from the players. It encodes an overall view of the strategy into a summary vector and is used to encourage the policy to follow a specific strategy by conditioning agents during supervised learning, and both conditioning and explicitly rewarding agents during reinforcement learning.

The statistic \(z\) consists of each player’s cumulative statistics and build order.

- The cumulative statistics are a 1-hot vector of whether or not each unit, building, effect (e.g., a force-field, which is produced by a special ability), or reach upgrade was present at any point in the game, which gives a high-level overview of the strategy the player executed.

- The build order is the first 20 units and buildings the player constructed during the game, as well as the positions of the buildings. Building orders are a common way of summarizing a player’s opening strategy in StarCraft.

Agents are conditioned only on \(z\) extracted from a randomly sampled replay of the top \(2\%\) players, and only from replays where the match-up and map matches the one the agent is currently playing.

One limitation of this formulation of \(z\) is that strategies in StarCraft are reactive, and depend on the observation of the opponent strategy, so while agents may be diverse they may not be sufficiently reactive. Therefore, agents only use \(z\) during the training stage and do not use \(z\) during evaluation.