Introduction

We discuss an information-based reinforcement learning method that explores the environment by learning diverse skills without the supervision of extrinsic rewards. In a nutshell, the method, namely DIAYN(Diversity Is All You Need), establishes the diversity of skills through an information theoretic objective, and optimizes it using a maximum entropy reinforcement learning(MaxEnt RL) algorithm(e.g., SAC). Despite its simplicity, this method has been demonstrated to be able to learn diverse skills, such as walking and jumping, on a variety of simulated robotic tasks. Moreover, it is able to solve a number of RL benchmark tasks even without receiving any task reward. For more interesting experimental results, please refer to view videos.

Diversity Is All You Need

In addition to general MDP, DIAYN further defines a skill as a latent-conditional policy that alters the state of the environment in a consistent way. Mathematically, a skill is denoted by \(p(a\vert s,z)\), where \(z\) is a latent variable sampled from some distribution \(p(z)\). The method is mainly built on three ideas

- For skills to be useful, we want the skill to dictate the states that the agent visits. Different skills should visit different states, and hence be distinguishable. To achieve this, we maximize the mutual information \(I(S;Z)\) between states \(S\) and skills \(Z\).

- We want to use states, not actions, to distinguish skills, because actions that do not affect the environment are not visible to an outside observer. This is done by minimizing the mutual information \(I(A;Z\vert S)\) between actions \(A\) and skills \(Z\) given the state \(S\).

- We encourage exploration and incentivize the skills to be as diverse as possible by learning skills that act as randomly as possible. Skills with high entropy that remain discriminable must explore a part of the state space far away from other skills, lest the randomness in its actions lead it to states where it cannot be distinguished. We achieve this by maximizing the policy entropy \(\mathcal H(A\vert S)\).

Now we put together all three objectives

\[\begin{align} \max\mathcal F(\theta):=&I(S;Z)+\mathcal H(A|S)-I(A;Z|S)\\\ =&\mathcal H(Z) - \mathcal H(Z|S)+\mathcal H(A|S)-\mathcal H(A|S)+\mathcal H(A|S,Z)\\\ =&\mathcal H(Z) - \mathcal H(Z|S)+\mathcal H(A|S,Z)\tag{1} \end{align}\]We now develop some intuitions on each term. The first term encourages our prior distribution \(p(z)\) to have high entropy. For a fixed set of skills, we fix \(p(z)\) to be a discrete uniform distribution guaranteeing that it has maximum entropy. Minimizing the second term suggests that it should be easy to infer the skill \(z\) from the current state. The third term suggests that each skill should act as randomly as possible.

The third term can be easily achieved with some MaxEnt RL method(e.g. SAC with temperature \(0.1\) used in their experiments). As for the first two terms, the authors propose incorporating them into a pseudo-reward

\[\begin{align} r_z(s,a):=\log q_\phi(z|s)-\log p(z) \end{align}\]where a learned discriminator \(q_\phi(z\vert s)\) is used to approximate \(p(z\vert s)\), which is valid since

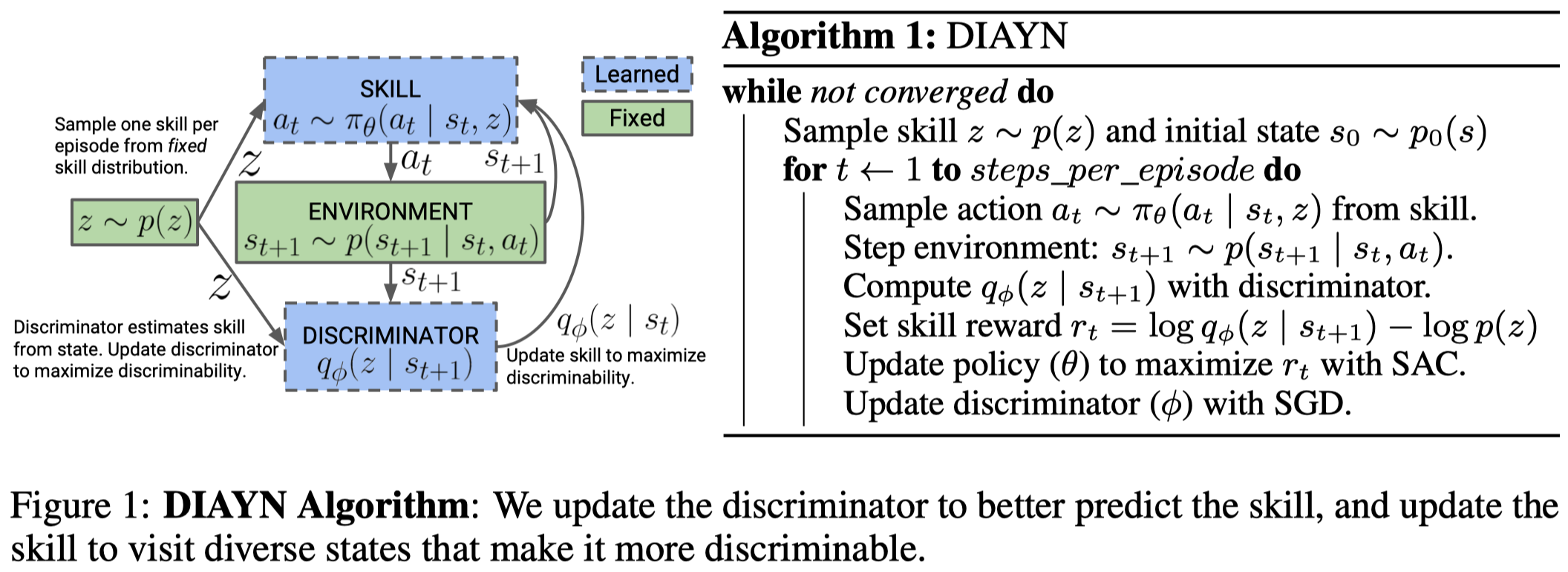

\[\begin{align} \mathcal H(Z) - \mathcal H(Z|S)&=\mathbb E_{s,z\sim p}[\log p(z|s)-\log q_\phi(z|s)+\log q_\phi(z|s)-\log p(z)]\\\ &=D_{KL}(p(z|s)\Vert q_\phi(z|s))+\mathbb E_{s,z\sim p}[\log q_\phi(z|s)-\log p(z)]\\\ &\ge \mathbb E_{s,z\sim p}[\log q_\phi(z|s)-\log p(z)] \end{align}\]Note that Figure1 conditions \(q_\phi\) on \(s’\), which makes the reward action-dependent. However, the rest of the paper as well as the implementation conditions \(q_\phi\) on \(s\). This difference is non-trivial: when we condition \(q_\phi\) on \(s\), we reward the agent for landing in \(s\); when we condition \(q_\phi\) on \(s’\), we reward the agent for taking action \(a\). Mathematically, we have \(\log q_\phi(z\vert s)=\mathbb E_{a, s’}[\log q_\phi(z\vert s’)]\). Regarding the definition of the Bellman equations, it makes more sense to use \(\log q_\phi(z\vert s’)\) as the reward function.

Note that the constant \(\log p(z)\) plays a nontrivial role in the reward function; it helps encourage the agent to stay alive on the right state since \(q_\phi(z\vert s)\ge p(z)\) ensures the reward function is always non-negative. On the other hand, removing \(\log p(z)\) results in negative rewards, which tempts the agent to end the episode as quickly as possible.

Algorithm

Until now we have defined the unsupervised MDP, and specified the reinforcement learning method, it is easy to figure out the whole algorithm:

\[\begin{align} &\mathbf{while}\ not\ converged\ \mathbf{do}:\\\ &\quad\text{Sample skill }z\sim p(z)\\\ &\quad\text{Sample trajectories and compute skill reward }r_z(s_t,a_t)=\log q_\phi(z|s_{t})-\log p(z)\\\ &\quad\text{Update policy }\pi_\theta(a|s,z)\text{ to maximize }r_z\ \mathrm{with\ SAC}\\\ &\quad\text{Update discriminator }q_\phi(z|s)\text{ through supervised learning} \end{align}\]Incorporating DIAYN into Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning

Networks learned by DIAYN can be used to initialize a task-specific agent, which provides a good way for initial exploration. Another interesting application of DIAYN is to use the learned skills as low-level policies of a hierarchical reinforcement learning algorithm. To do so, we further learn a meta-controller that chooses which skill to execute for the next k steps. The meta-controller has the same observation space as the skills and aims to maximize the task reward.

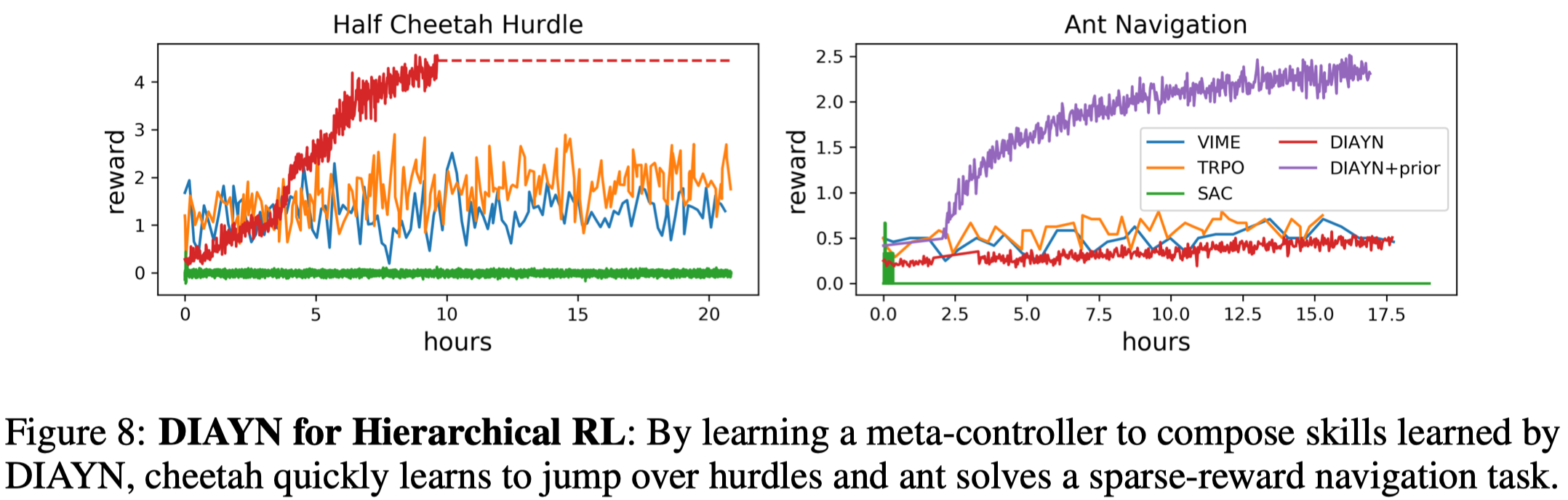

The authors experiment the HRL algorithm on two challenging simulated robotics environments. On the cheetah hurdle task, the agent is rewarded for bounding up and over hurdles, while in the ant navigation task, the agent must walk to a set of 5 waypoints in a specific order, receiving only a sparse reward upon reaching each waypoint. The following figure demonstrates how DIAYN outperforms some state-of-the-art RL methods.

It is worth noting that plain DIAYN struggles on the ant navigation task like the others. This can be remedied by incorporating some prior knowledge into the discriminator. That is, the discriminator \(q_\phi(z\vert f(s))\) instead takes as input \(f(s)\) that computes the agent’s center of mass and the HRL method is left as it is. ‘DIAYN+prior’ shows this simple modification to the discriminator significantly improves the performance.

We compare this method with SAC-X:

- SAC-X learns a set of hand-designed auxiliary tasks(including the main task), while DIAYN learns a set of skills by simply maximizing the diversity. As a result, DIAYN is more likely to establish some unexpected novel behaviors.

- SAC-X distinguishes different policies using different heads, while DIAYN learns a single latent-conditioned policy.

- The scheduler in SAC-X plays a similar role as the meta-controller in hierarchical DIAYN does. But SAC-X only uses the scheduler at the training time to accelerate the learning process and no longer requires it at the test time. This difference makes the meta-controller in DIAYN more complex than the scheduler in SAC-X.

Discussion

Is the meta-controller trained at the same time DIAYN is trained?

I personally do not think so. In fact, the hierarchical DIAYN proposed by the authors is almost the same as HIRO, except for the definition of goal and low-level reward. This suggests that if we train the low-level policy and the meta-controller together through an off-policy algorithm, we have to relabel the latent, which is hard since the latent is discrete and worse still it does not have the same practical meaning as the goal in HIRO.

References

Benjamin Eysenbach et al. Diversity is All You Need: Learning Skills without a Reward Function